Today’s cinema adventure: Peeping Tom, the controversial 1960 thriller directed by Michael Powell, who was one of Great Britain’s most revered and respected filmmakers- that is, until the savage critical lambasting received by this feature effectively put an end to his career. Photographed in garish color reminiscent of the lurid under-the-table pornography of its time, this tale of a disturbed young recluse who films women as he murders them was such a flop upon release that it was barely shown outside of England. Over the succeeding years, however, it became a cult classic, growing in critical estimation and championed by such heavy hitters as Martin Scorsese (for one), and it is now generally acknowledged as a ground-breaking, underappreciated masterpiece of the genre. On an intellectual level, I can see why: director Powell thoroughly explores the theme of voyeurism as it applies to cinema, forcing the audience from the very first frames to identify with the killer, and using the film’s story as a vehicle to manipulate our sympathies, uncover our own guilty voyeuristic tendencies, and confront us with our darkest fears just as his protagonist does with his victims. There isn’t an extraneous or gratuitous moment in the film; every scene, every frame, every shot is calculated and geared toward the purpose- a testament to Powell’s mastery of his cinematic medium. Despite the high score on an academic level, however, the film falls short for me on the more visceral level of emotional response; part of this may be due to the fact that, after 50 years, the film’s shock value (and body count) has been far surpassed by countless other horror movies and, by today’s standard, seems fairly tame (albeit still quite unsettling on a psychological level). But I think the primary problem lies with the casting of Carl Boehm in the central role of the homicidal cameraman: not only does his German accent seem out of place for this decidedly English character, but his performance is stilted and unconvincing, making it difficult for us to sympathize with him- a necessary element to the transference of guilt to the audience which Powell works so hard to achieve. The rest of the cast is excellent (particularly the young Anna Massey and the film’s biggest star, Moira Shearer, whose small but pivotal role is the centerpiece of the film’s most masterful and harrowing sequence), but with Boehm’s wooden presence in the middle of the proceedings, the film’s overall effect is muted: it stimulates the brain, and disturbs the psyche, but the heart remains aloof. Still, it has much to recommend it, and it’s definitely worth the effort to check out a movie which, flawed or not, remains as an important footnote in cinematic history.

Monthly Archives: June 2012

Thor (2011) & Captain America: The First Avenger (2011)

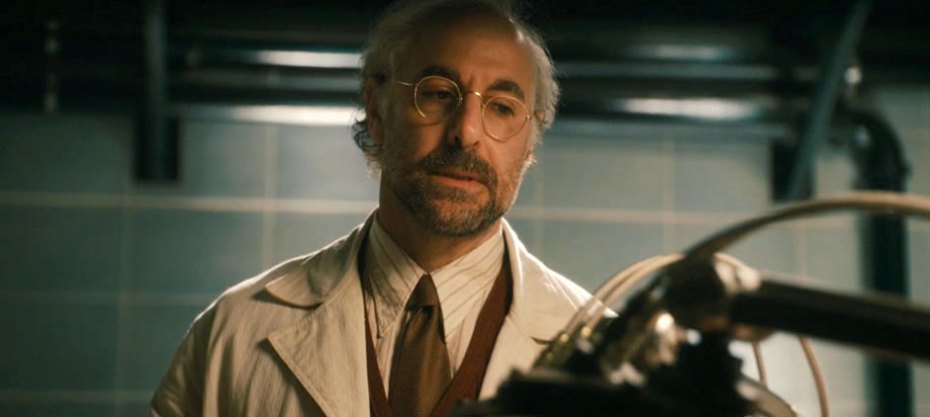

Today’s cinema adventure is a double feature: Thor and Captain America: The First Avenger, the two 2011 entries from Marvel that introduced audiences to seminal figures in the then-upcoming Avengers blockbuster, further establishing the groundwork begun in the successful Iron Man franchise and setting up key elements of the story arc which unites all the films. In the first of the pair, Thor, heir to the throne of Asgard, is exiled by his angry father to the distant planet earth, precipitating a rebellion in his home world which threatens to wreak destructive havoc in both places; in the second, set during the second world war, scrawny weakling Steve Rogers is transformed by a secret government experiment into a super soldier who leads the battle against an insidious threat rising from within the ranks of the Nazi Reich. The two films bookend each other nicely, thematically speaking: both feature heroes who rise to greatness, one by breaking through his own arrogance to find humility; and the other by holding on to his pure-hearted nature after being bestowed with super-human powers. Both scenarios are familiar variations of the “Hero’s Journey” myth, and as such fit snugly into the comic book milieu from which the characters and their stories are drawn; and though the production teams for each film are, for the most part, comprised of different artists, under the guidance of Marvel and its mastermind, Stan Lee, both maintain a strong visual and thematic connection to the printed form of the source material. Indeed, thanks to the heavy use of CG effects in creating the worlds of these films- which at times almost erases the line between animated and live action filmmaking- they seem like gigantic, moving comic books; the only thing missing is the presence of bubbles for the dialogue and thoughts of the characters. This, of course, is precisely what the creators of these spectacles have intended; and on that level, they have succeeded in spades. However, it is that candy-coated quality that handicaps both of these films, as well: in making the impossible come to life in such a clearly artificial setting, they distance us from the characters and the story, keeping us constantly reminded that what we are seeing has no real weight or consequence in our lives and preventing an emotional connection much in the way that Brechtian theatre-of-alienation tactics were designed to do; unfortunately, the purpose of that presentational technique was to provide a detachment that would allow an intellectual connection instead, and here, there is so little food for thought that the effect (for those not dazzled into submission by the visual trickery) is closer to boredom. Between the two films, Thor fares somewhat better: though marginally more far-fetched in its content, the mythological connection provided by its use of Norse gods and goddesses as an integral part of the plot allows us, somehow, to more comfortably suspend our disbelief and buy into its premise of our world being caught up in a conflict of all-powerful titans. Indeed, the storytelling aspect is strong enough- almost- to avoid being overwhelmed by the computer-rendered spectacle surrounding it, largely thanks to the direction of one-time Shakespearean golden-boy Kenneth Branagh, whose extensive experience with classical narratives makes him well-suited to the mythic themes in play. Not so sure-handed at the helm is Joe Johnston, whose Captain America starts out well enough as it chronicles the eager young hero’s transformation, but then seems to move aimlessly through its progression of set pieces, content to rely on action and mood to keep us interested until it reaches the last one; rather than the unfolding of an archetypal tale, this second film feels instead like a piece of nostalgic fluff, a cliché-ridden WWII adventure souped-up with wish-fulfillment fantasy, trying painfully hard to avoid irony in its handling of the gee-whiz jingoism of its subject matter by masking it in nostalgia (mainly provided by the bathing of every scene in a golden-hued light in order to remind us that we are watching a story set in the 1940s). This lack of real direction is exacerbated by the hollowness of the characters: whereas in Thor, the screenwriters (Ashley Miller, Zack Stentz, Don Payne) invest time and attention to the development the characters and their relationships, in Captain America the scribes (Christopher Markus, Stephen McFeely) have relied on the familiarity of the stock types that populate their film, establishing identity with glib one-liners and giving mere lip service to the bonds and rivalries that determine their loyalties; in both, the players are little more to us than obligatory ciphers required to fulfill a formula, but at least in Thor, they have real personality. The cast lists of both movies are dotted with ringers: such heavy hitters as Anthony Hopkins, Stellan Skarsgârd and Natalie Portman (Thor) and Tommy Lee Jones, Stanley Tucci and Hugo Weaving (Captain America) all add prestige and interest to the proceedings, and manage- with varying degrees of success- to elevate the material to a level that at least gives the illusion of substance. As for the titular heroes, Chris Hemsworth as Thor does an adequate job of enacting his transformation from entitled blowhard to compassionate champion, and Chris Evans as the Captain manages to capture the right blend of sincerity and aloofness; but, perhaps partly due to the inherent limitations of the characters, both actors ultimately comes off as little more than eye candy (not that this is a bad thing- part of the traditional appeal of this kind of escapist entertainment is the beefcake factor). The production of both movies, as mentioned before, is breathtaking, presenting us with glossy, hyper-real visions of the Marvel Universe; united by cohesive production design (Bo Welch for Thor, Rick Heinrichs for Captain America), they continually wow us with movie magic that reminds us of how far we’ve come from the days of actors hanging on wires in front of projected skyscapes. The musical scores, provided by Patrick Doyle (director Branagh’s long-time collaborator) on Thor and Alan Silvestri on Captain America, are appropriately stirring. In fact, every technical aspect of both films is top-notch, Grade-A, best-of-Hollywood stuff; but ultimately, though Thor has its strengths, they both come up short in the long run, big on style and spectacle, but lacking in the kind of genuine depth that can make movies of this genre into a more meaningful experience. There is certainly entertainment value here, but even that seems strangely lacking; both pieces feel more like prologues (which they are) than stand-on-their-own experiences, setting the stage for things to come and somehow failing to provide the satisfaction of real closure. Of course, this is the nature of comic books- each segment ends in a cliff-hanger, ensuring that the reader will rush out to buy the next edition as soon as it is available. Thankfully, in this case the next edition is The Avengers, which succeeds where these two predecessors have not- but that’s another review.

Thor http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0800369/

Captain America: The First Avenger http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0458339/

—————————————————————-

The Ritz (1976)

Today’s cinema adventure: The Ritz, the 1976 screen version of Terence McNally’s daring-for-its-day stage farce about a straight Midwestern businessman who hides out from his homicidal brother-in-law by checking into a gay Manhattan bathhouse. Directed by the legendary Richard Lester (known for a fast-paced, edgy style that made The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night into an instant classic) with a screenplay by the playwright himself, the film has aged into something of a curiosity of its time- a glimpse at bathhouse culture during the heady pre-AIDS era of the sexual revolution. McNally (who has become something of a gay poet laureate) made the brilliant move of taking the formula of a classic farce and placing it into what was at the time (and, sadly, to an extent, still is) a socially taboo setting; the result was a risqué piece of popular entertainment which brought underground gay culture into the spotlight and ostensibly took a small step towards making homosexual subject matter more acceptable for mainstream audiences. Unfortunately, by virtue of the requirements of the farcical genre, the characters (both gay and straight) are one-dimensional stereotypes which seem tired and offensive today, and the comedy has been rendered considerably less amusing by years of over-exposure to TV sit-coms in constant rotation. The highlight of the film is undoubtedly Rita Moreno, reprising her Tony-winning Broadway performance as Googie Gomez, a fiery Bathhouse Betty who gets caught up in the intrigue and (fortunately for the audience) performs a deliciously over-the-top lounge act for the boys; also of note are her Broadway co-stars, Jack Weston (as the hapless refugee), Jerry Stiller and future Oscar-winner F. Murray Abraham (as a flaming, self-appointed tour guide who manages to be likeable despite the heaping load of gay clichés he is required to carry), and an amusing turn by a young Treat Williams as a naïve (and squeaky-voiced) private detective. The rest of the cast fill their roles sufficiently well, Lester’s direction is sure-handed, and the look and feel of the seedy setting are captured quite authentically- but in 2012, the edge which once made it all so delightful has become painfully dull. The bottom line: as a piece of social and theatrical history, The Ritz is definitely important enough to warrant a viewing; but if you are just looking for some laughs and entertainment, you might want to skip it- or, better yet, fast forward to Rita’s scenes and just watch those.

Young Adult (2011)

Today’s cinema adventure: Young Adult, the 2011 feature by writer Diablo Cody (Juno) and director Jason Reitman (Up in the Air). Charlize Theron stars as Mavis, a hard-drinking thirty-something writer of teen romance novels, who attempts to resolve her fractured emotional life by returning to her small hometown and stealing her former high school sweetheart away from his wife and infant daughter. Ostensibly a dark comedy, this piece is in fact a character study- and a bleak one- which hinges on the performance of Theron as its central character, and she rises brilliantly to the occasion. The actress won an Oscar for playing a serial killer in Monster, and she equals that work here with her portrait of another kind of “monster,” an alcoholic whose arrested emotional development has her teetering on the brink of self-destruction, trying to use prom queen tactics in a grown-up world and unconcerned with the havoc she wreaks on the lives of those around her; but, even as Mavis’ downward spiral becomes increasingly embarrassing and her behavior grows more and more hateful, Theron succeeds in capturing the spark of humanity that allows us to see through the affectation and attitude to which she so desperately clings, and makes it possible, if not to sympathize with her, at least to understand her- and, a little unsettlingly, even to relate to her. Providing a counterpoint to Mavis’ delusional shenanigans is Patton Oswalt, as an old schoolmate (disabled by a savage beating which may have been at least partly her fault) whose ability to see through her façade makes him both an antagonist and an unlikely ally; he delivers an unsentimental performance that keeps the character likeable while still underlining the dysfunctions that affect his own broken life. Patrick Wilson, as the object of Mavis’ obsessions, is cast once more as the stolid-but-faded golden boy, a part which he fills to a tee- though it would have been nice to see his character laced with a little more of the darkness he has so brilliantly essayed in similar roles (Angels in America, Little Children, Watchmen). The remainder of the cast is largely relegated to the background, where they serve as foils for the one-woman-show they surround; indeed, one of the film’s most significant characters is the scenery itself, an authentically realized small-town suburbia full of the bland and familiar icons of Middle American life, which provides a constant reminder of the comforting-and-maddening mediocrity from which- or to which- so many of us wish to escape. As for the work of the film’s masterminds, Cody’s screenplay is full of the kind of edgy hipster irony we have come to expect from her, infusing the dialogue with a double-edged wit that makes us cringe even as we chuckle; and Reitman’s direction displays his easy skill with visual storytelling, effortlessly blending revelatory character detail and thematic reinforcement within the straight-and-steady unfolding of the narrative. It should be said, however, that Young Adult, though strong on observation, comes up a bit short when it comes to insight; in the end, despite the exposure of numerous key moments in Mavis’ life, we are really no closer to understanding what makes her tick. Still, perhaps it is wrong to expect easy answers in a story about an alcoholic’s decline; and even though Young Adult lacks the disarming freshness of Juno or the unexpected emotional resonance of Up in the Air, both its creators deserve considerable praise for making a film brave enough to favor realism over sentiment by refusing to redeem or resolve. Though there are plenty of genuine laughs here (albeit somewhat morbid ones), this film is not for the squeamish; the rest of us, however, will be refreshed by the rare honesty behind it- and rewarded by the magnificent performance of its leading player, who continues to prove that, as beautiful as she is, it is her talent that makes her a star.

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011)

Today’s cinema adventure: We Need to Talk About Kevin, the disturbing and controversial 2011 feature based on Lionel Shriver’s award-winning 2003 novel of the same name. Tilda Swinton stars as Eva, a woman haunted by memories and repercussions as she attempts to come to terms with the horrific acts committed by her teenaged son. As directed by BAFTA-winner Lynne Ramsay, the film draws us in from its very first moments with arresting visuals and an enigmatic soundscape, unfolding its nightmarish story through a non-sequential progression of scenes and images that gradually piece together like the shattered fragments of Eva’s life. It’s riveting stuff: Ramsay (who also co-wrote the screenplay with husband Rory Kinnear) keeps us engaged and unsettled throughout, saturating us with stylish imagery marked by an ingenious use of color (with a decided emphasis on red, maintaining an ever-present suggestion of blood), layering in just enough foreshadowing and clues to conjure a growing sense of dread over the inevitable conclusion, infusing each scene with an atmosphere of resigned melancholy and foreboding, and dominating the proceedings with an uneasy silence which is only broken by spare, terse dialogue that shocks and pierces as much as it informs. As we observe Eva’s disjointed recollections and her nightmarishly surreal day-to-day life, we find ourselves drawn into her psyche; forced to face the uncomfortable- and unanswerable- questions raised about the culpability of a parent in the wrongs committed by their offspring; and in the end, the biggest question may be how to find a resolution, a sense of closure which can permit the lives of those left standing to go on- and if, indeed, such a thing is even possible. With all these psychological themes in play, one might be tempted to consider We Need to Talk About Kevin to be a complex drama, but make no mistake about it: this is unquestionably a horror film, the kind of nightmarish thriller that is rarely made these days. It follows no pre-molded formula, and there are none of the expected clichés of the genre: no sudden shocks, no scantily-clad female victims screaming as they flee through the dark night, no oceans of gore (for all the red flowing across our eyes, there is very little blood or violence onscreen, with Ramsay opting instead to paint the horrible pictures in our imagination where they are infinitely more disturbing). This is not some schlocky shocker designed for a teenagers’ date night, but rather, like other great adult horror films of the past such as The Exorcist or Rosemary’s Baby, it is an exploration of evil in our lives, of how it manifests and what might be its causes; but unlike the aforementioned classics, there is no suggestion here of supernatural forces- the responsibility is placed squarely on human shoulders, with implications that are far more chilling than the presence of any demonic scapegoat. It would be easy, in the wrong hands, for Kevin to veer off into the realm of exploitative trash; but not only is Ramsay well-equipped for the task, she has the considerable benefit of Tilda Swinton in the central role. Swinton has proven many times that she is one of the most electrifying screen performers working today, and here she solidifies that reputation with a stunning, solid portrayal of a woman for whom the joy of motherhood has been inverted into a nightmare. With a minimum of dialogue, she conveys Eva’s harrowing journey with masterfully subtle changes in her continuous expression of dull shock, bringing home the frustration, the terror, and the loneliness created by the growing comprehension that her child is a monster and she alone can see it. It’s a tour-de-force performance, and its failure to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress- particularly when it was recognized by virtually every other major awards organization- was surely one of the great injustices of Oscar history. Supporting Swinton’s magnificence is John C. Reilly, likeable but obtuse as Eva’s husband, a man whose doting denial helps to enable the ever-escalating sociopathy of their son and drives an immovable wedge into their marriage; and a shining turn by Ezra Miller as the title character, who skillfully avoids the temptation of playing for sympathy- this is no misunderstood, angst-ridden adolescent, but a young cobra smugly and gleefully coiling up for a fatal strike. Mention is also deserved for Jasper Newell, as the six-to-eight year-old Kevin, who eerily projects a malicious menace beyond his years, somehow making the younger incarnation even more frightening than his future self. In addition to the stellar cast, Ramsay is aided in her vision by superb work from her technical collaborators: an eerie and atmospheric score by Johnny Greenwood (of Radiohead) meshes seamlessly with the carefully orchestrated sound design by Paul Davies; the cinematography by Seamus McGarvey provides some of the most vividly realized images in recent film memory, into which the simple-yet-striking costume design of Catherine George is brilliantly coordinated; and the editing by Joe Bini is a masterpiece of visual juggling, managing to maintain a steady flow throughout a narrative which freely jumps forward and back to multiple periods in time. It is a shame- but not a surprise- that We Need to Talk About Kevin has yet to recoup the $7 million that was spent to make it; you can chalk it up as yet another sign that the contemporary film market is driven by an increasingly less sophisticated mindset, but this would be a difficult film to sell in any era, really. It is a psychological thriller that dares to address deeply disturbing issues which most of us would prefer to keep out of sight and out of mind, and watching it is a grim and unrelenting experience which may leave you disturbed for days afterward. If that sounds as good to you as it does to me, We Need to Talk About Kevin is a film you must not miss.

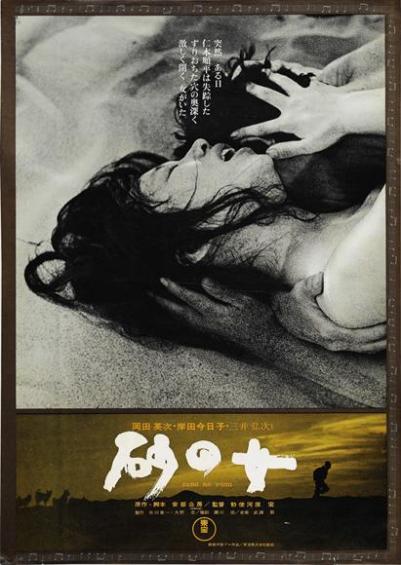

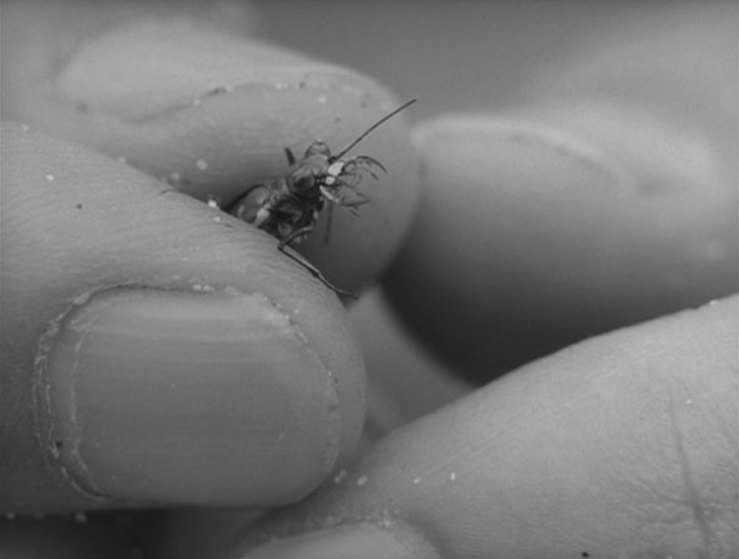

Woman in the Dunes/Suna no onna (1964)

Today’s cinema adventure: Woman in the Dunes the strikingly photographed 1964 avant garde feature by Japanese filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara, Adapted by Kōbō Abe from his own novel, it’s a deceptively simple parable about an entomologist on a field expedition to collect specimens at a remote beach; when he misses his return bus, he seeks shelter for the night with a young widow in a local village- only to find himself trapped into remaining as her companion in a life of endless labor, shoveling sand from the quarry in which they live, both for their sustenance and to prevent their house from being buried. Within the framework of this premise are explored a multitude of giant, deeply reverberating themes, ranging from the contrast between the masculine and the feminine to man’s role in society to the very nature and meaning of existence itself- all of which plays out against the backdrop of the monumental, ever-shifting sand dunes, emphasizing the inexorable dominance of nature and the universe and transforming the primal landscape into a central character of the drama. The performances of the two principals (Eiji Okada and Kyoko Kishida) are superb, helping to create the delicate balance between realism and symbolic fantasy that propels the film- but the true star here is the magnificent black-and-white cinematography of Hiroshi Segawa, which not only captures the fluid, omnipresent sand in remarkable, crystalline detail, but conveys a sense of tangibility to every texture in the film, from the salty grit which covers every surface to the smoothness of the players’ skin, making the viewer’s experience highly visceral- and erotic. One of those world cinema classics that is a staple in film classrooms around the world, the artistry of Woman in the Dunes is indisputable- some audiences, however, may find that its blend of existential absurdism and Zen austerity creates a cool detachment that prevents emotional involvement in the action. Nevertheless, as an intellectual and philosophical exercise- and as piece of stunning visual artistry- it’s a film which packs more than enough power to make its 2 ½ hour running time seemingly fly by. A must-see for any serious film buff- but you may feel like you need a long shower to rinse off all that sand.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Today’s cinema adventure: The Man Who Fell to Earth, Nicholas Roeg’s 1976 feature starring David Bowie in his first leading film role. Based on a 1963 novel by Walter Tevis, it tells the story of Thomas Jerome Newton, an extra-terrestrial visitor who uses his advanced technology to build an enormous fortune, with the intention to finance the transport of water back to his drought-ravaged home planet, only to be trapped by the interference of corporate and governmental forces- and by his own indulgence in the pleasures of an earthly lifestyle. Visually arresting, leisurely paced, solemn and thoughtful in tone yet experimental and occasionally sensational in style, Roeg’s film (like it’s protagonist) is something of an enigma. Eschewing clarity for mood, the director obscures the storyline with surreal imagery depicting the visceral experiences of its characters, flashbacks to the blasted desert landscape of Newton’s world, strange episodes of temporal disturbance, and a continual shifting of focus among the perspectives of the various principals. The result is a disjointed, confusing film which seems designed to make sense only upon repeated viewings, with plot points revealed in passing by off-handed dialogue, the omission of key details which forces them to be filled in by audience assumption, and the ambiguous resolution of major story elements which leaves more questions than answers. These, however, are deliberate moves on Roeg’s part; he is less interested in presenting a cohesive science fiction narrative than in exploring a metaphor about the lure of wealth and pleasure and the corruptive influences of social and political forces, and he expresses these themes through a meticulously edited mix of hallucinogenic, serene, majestic and pedestrian images which blend to create a dreamlike final product. As for the acting, the key supporting roles are effectively filled by experienced pros Rip Torn and Buck Henry, as well as seventies flavor-of-the-day starlet Candy Clark as a blowsy hotel housekeeper who becomes Newton’s companion; but the film is, of course, centered on Bowie, here at the height of his rock icon popularity, who provides the perfect blend of childlike simplicity and jaded sophistication, exuding both poise and vulnerability and projecting the haunted longing and the bitter disillusionment that mark Newton’s odyssey through the experiences of our planet. Bowie himself has admitted to his heavy use of cocaine during the making of the film, which (though regrettable from many viewpoints) no doubt served to enhance the dissociated, alien persona which so perfectly complements its dreamy, distant mood. Added to the mix is superb cinematography by Anthony Richmond (which dazzlingly captures, among other things, the beauty of the New Mexico landscape that provides the setting for much of the film) and a well-chosen soundtrack of music (compiled by ex-Mamas-and-Papas-frontman John Phillips) featuring avant garde compositions and familiar pop tunes from various eras. The bottom line on this cult classic: if you are looking for a straightforward sci-fi tale, don’t look here- although the currently available version is a restored director’s cut which makes the plot somewhat more coherent than the highly-edited original release, you are almost guaranteed to be disappointed. However, if you are interested in a thought-provoking visual experience (or if you are a hardcore Bowie fan), this really is a must-see, and though it is ultimately somewhat cold and unsatisfying, it is a film which will stay with you for a long time afterwards.

Crimes of Passion (1984)

Today’s cinema adventure “Crimes of Passion, the controversial 1984 sexual thriller by cinematic bad-boy Ken Russell, centered around a hard-driven career woman who gets her sexual validation moonlighting- in disguise- as a streetwalker named “China Blue.” With his characteristic excess, both in his artistic style and his explicit depiction of sex, Russell uses the titillating scenario to explore a variety of psycho-sexual themes, portraying attitudes and behavior at both ends of the spectrum between depravity and repression; provoking numerous questions about the relationships between love, sex, truth, fantasy, shame, guilt and redemption; and exploring the difficulty of overcoming fear and immaturity in order to form an honest human connection. A heady and ambitious agenda, to be sure, and whether or not Russell and his screenwriter/producer, Barry Sandler, have succeeded in achieving it is still the subject of much debate- as with most of the director’s work, the response of critics and audiences is sharply divided between “hate it” or “love it.” My take: Russell’s madness has a method, and with his almost cartoonish depiction of the erotic underworld inhabited by China Blue and her clientele, he highlights the absurdity of our sexual prejudices and suggests that we have much more to fear from the consequences of repressing our natural desires. Helping considerably towards this goal is Kathleen Turner, at the height of her sexual appeal, delivering a remarkable performance infused not only with the necessary gleeful eroticism but also the vulnerability of a woman terrified by emotional intimacy. Also superb is Anthony Perkins, in an underrated turn as a seedy street preacher whose shame over his own pornographic impulses leads him to an obsession with “saving” China Blue; though derided by many critics as “over-the-top,” Perkins’ work here is frighteningly accurate, which should be clear to anyone who has ever had an encounter with a dangerously schizophrenic denizen of the streets. These two share several delicious scenes together, skillfully enacting an ongoing point/counterpoint about sexual morality that underscores the movie’s themes and provides many of its most delightfully melodramatic moments. Not as proficient is John Laughlin as a naive young husband whose failing marriage leads him to China Blue’s bed- but despite his somewhat stilted acting, his sincerity shines through enough to provide the necessary relief from the darkness of the skid row surroundings. Other notable elements include the costumes, scenic design and cinematography, all of which brilliantly contrast between the garish night-time world of the red-light district and the bland suburban daylight of the film’s other scenes- the two worlds seem almost as if they have been spliced together from two different films. Less successful- perhaps the film’s biggest flaw, really- is the tinny electronic score (provided by Rick Wakeman of the band Yes), which may have seemed like a good idea at the time but now provides a ludicrously dated atmosphere in a film that might otherwise seem almost timeless. Nevertheless, Russell’s film retains a surprising depth and resonance despite- or perhaps because of- the sensationalism of its hyper-sexual surface, and even if there are times when his intellectualism threatens to undermine the plot or his exploitative excess threatens to alienate his audience, the compelling performances of his two stars succeed in maintaining the emotional connection that is necessary to ensure the slow build of suspense into the climactic scenes. Overall, though Crimes of Passion lacks the audacious mastery that made instant classics of some of Russell’s earlier works, it still packs a powerful punch, melding sensuality with horror and humor with high drama, and ultimately- in my view anyway- standing as one of the most memorable and unique films of the eighties.

The Avengers (2012)

Today’s cinema adventure: The Avengers, the long-awaited 2012 action/fantasy feature from director Joss Whedon which unleashes the combined force of most of Marvel’s top superhero characters and has ensured, with its record-smashing box office returns, that the flourishing “comic book” genre is here to stay- at least for now. The plot, of course, could have been lifted from any Cold-War-era sci-fi potboiler: when a god-like being from another world brings an army to conquer the earth, a secretive government organization assembles a band of disparate heroes to head off the invasion, forcing them to set aside their own differences- and face their own weaknesses- in order to unite against the common foe. The details get a bit confusing, unless you are intricately familiar with the plot threads that have been unwinding through the various associated franchises leading up to this blockbuster, or unless you can follow the lightning-fast pseudo-technical jargon with which the various conceits are established; but none of that matters, because unlike many inferior attempts at making this sort of hyper-driven action spectacle, “The Avengers” hinges not on its ridiculous storyline- nor even on the mind-blowing, state-of-the-art special effects, though admittedly those provide a considerable amount of the fun- but on the characters which inhabit it. The legion of “fan boys” at which this movie is targeted can rejoice that, after decades of clueless studio hacks trying to capitalize on the popularity of comic books without understanding or respecting the material, at long last the genre is in the hands of artists who have grown up with a reverence for it; gone are the days of bland, leotard-clad goofballs with no charisma spewing cheesy platitudes. Here we are treated to a collection of heroes that we can truly believe in because we can relate to them: full of doubts, anger, trust issues and guilty consciences, they are nevertheless driven by hope to perform the duties thrust upon them; and there is never any question that they have the ability to face whatever the other-worldly would-be conquerors can throw at them, as long as they can overcome the obstacles they generate within their own flawed psyches. By capturing this element, Whedon (who also wrote the screenplay, from a story by himself and Zak Penn) has captured the key to what makes these far-fetched, over-the-top stories so compelling: they are, in fact, mythology that has been re-invented in a form that appeals to a modern generation. We see our own psycho-dramas acted out in symbolic form by these idealized versions of ourselves, and through their victories we see the possibility of our own. To be sure, of course, it’s not the kind of doom-and-gloom mythology that takes us through the dark night of the soul, and it would be completely wrong to think that The Avengers aims at any emotional or spiritual resonance beyond an adolescent level; but still, no matter how many millions of dollars were spent on the CG eye candy, it would have all just been visual noise without that important, cathartic element. The Avengers seeks to entertain, not to enlighten, but it’s a testament to the talent of its creative forces that it manages to do both. Whedon has levied his success as a creator of niche-targeted cult entertainment into status as a mainstream artist to be reckoned with, and he directs with a sure hand and a clear vision, striking a perfect balance between action and intimacy and keeping the whole thing roaring along at a breathless pace that makes the two-hour-plus running time feel half as long. He has considerable help from crack film composer Alan Silvestri, cinematographer Seamus McGarvey, and an army of designers and special effects artists under production designer James Chinlund; and, of course, the work of his cast is exemplary, with the always-delightful Robert Downey, Jr., Mark Ruffalo, and Scarlett Johansson standing out in particular. Special mention must be made for the driving force behind it all: comic book legend Stan Lee (one of the Executive Producers of this and all the Marvel films, which are of course his babies), who has brought his remarkable work from the printed page to the big screen (in magnificent 3-D, no less) with meticulous attention to getting it right and a vision that invites comparison to, dare I say it, Walt Disney himself. Before I am accused of gushing, I should point out that there are quibbles to be made here- the villain, Loki, is not exactly an imposing threat, for all his superhuman powers, and there are numerous points in the film when the perfunctory conflicts between the protagonists threaten to derail the driving pace- and I can’t say that The Avengers and the other films with which it forms a sort of super-franchise (pardon the pun) transcend the comic book genre, as Christopher Nolan’s rebooted Batman cycle has done. Nevertheless, in a time when rising ticket prices make it less and less appealing to go to the theater rather than just wait a few weeks for the DVD/BluRay release, it’s a film that delivers what it promises and more; and that’s a feat at least as heroic as any of those accomplished by the superteam of its title.

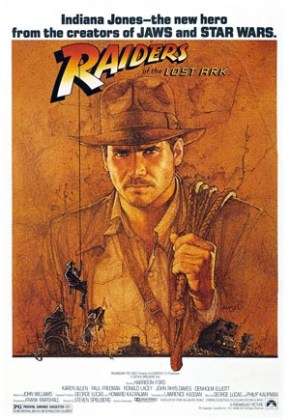

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Today’s cinema adventure: Raiders of the Lost Ark, Steven Spielberg’s 1981 action-adventure-fantasy paying homage to- and gently spoofing- the cliffhanger serials of the thirties and forties- but with the benefit of a mega-budget and then-state-of-the-art special effects, courtesy of the powerhouse production provided by George Lucas. It would be pointless and impossible for me to write anything like a critique of this film- it has passed beyond the realm of review and into cinema legend, and did so almost immediately upon release, becoming an instant classic and creating a brand new archetypal hero in Indiana Jones, the mercenary archaeologist/adventurer at its center. It spawned a franchise of three (mostly inferior) sequels, countless unworthy imitations, and it made an icon of its star, Harrison Ford, whose roguish charm melds so perfectly into his character that it is literally impossible to imagine anyone else playing it. And, on a personal level, it became a major touchstone in my young manhood, a cultural phenomenon into which I dove headlong, making any sort of objective viewpoint about the movie completely irrelevant. What I will say is that, after several years since my last viewing, the movie holds up brilliantly, seeming just as fresh and fun as it was 30 years ago, managing a precarious balancing act between the serious tone necessary to sustain its premise and the sly, unapologetic goofiness that keeps it fun and reminds us, constantly, that it’s only a movie- aided immeasurably by John Williams’ rousing, multi-faceted score, with its now-familiar thematic march, which is surely one of the greatest examples of the use of music to support and drive a film. In addition, it struck me this time around that this movie represents Spielberg’s direction at its finest, the work of a young artist at the height of his powers, using his skills for the sheer joy of it- completely without pretense or the need to make any kind of statement, merely an expression of his own love of movie magic and an invitation to us all to share it with him. Sure, you can quibble forever over the myriad gaps in logic and continuity that render the entire story ridiculous- an intentional element drawn from the grade-Z crowd-pleasers that inspired it- or you can point out the numerous visual and stylistic references to classic movies like Treasure of the Sierra Madre or Lawrence of Arabia, from which the director derived his filmmaking vocabulary; but those things don’t matter, in the final analysis. “Raiders” stands on its own as a great achievement in filmmaking, a timeless tribute to movies themselves and a magic potion to rekindle- even if only for a couple of hours- the adventurous imagination of the fourteen-year-old in us all.