Today’s Cinema Adventure originally appeared in

Today’s Cinema Adventure originally appeared in

For fans of filmmaker Wes Anderson, the arrival of a new movie by the quirky auteur triggers an excitement akin to that of a ten-year-old boy opening a highly-coveted new toy at Christmas. For them, something about the director’s style conjures a nostalgic glee; the puzzle-box intricacy with which he builds his cinematic vision combines with the detached whimsy of his characters to create an experience not unlike perusing a cabinet of curiosities, bringing out the viewer’s inner child and leaving them feeling something they’re not quite sure of for reasons they can’t quite put their finger on.

Those who love his work – and there are a lot of people in this category – find it immensely satisfying.

Those who don’t are left scratching their heads and wondering what the point was to all that tiresome juvenilia.

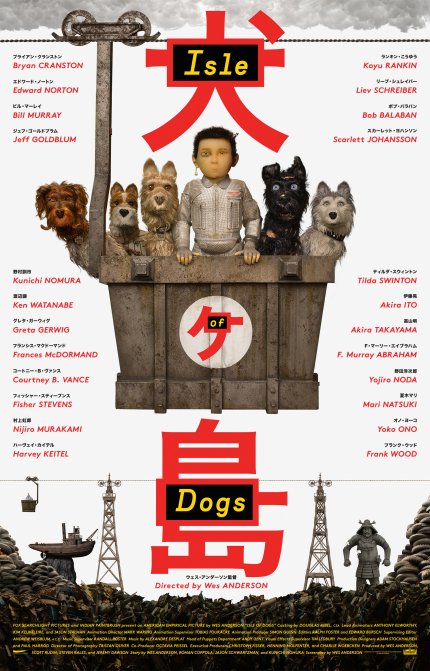

Anderson’s latest, “Isle of Dogs,” is likely to meet just such a split in opinion – and this time, thanks to accusations of cultural appropriation, marginalization, and outright racism, it’s not just about whether you like the directorial style.

His second venture into the field of stop-motion animation (the first was “Fantastic Mr. Fox” in 2009), it’s an ambitious fable set in a fictional Japanese metropolis named Megasaki, twenty years into the future. The authoritarian mayor, the latest in a long dynasty of cat-loving rulers, has issued an executive decree that all the city’s dogs must be exiled to “Trash Island” – including Spots, the beloved pet and protector of his twelve-year-old ward, Atari. The boy steals a small plane and flies to the island, where he enlists the aid of a pack of other dogs to help him rescue Spots from the literal wasteland to which he has been banished. Meanwhile, on the mainland, a group of young students works hard to expose the corrupt mayor and the conspiracy he has led to turn the citizens against their own dogs.

In usual fashion, Anderson has made a film which expresses his unique aesthetic, marked with all his signature touches: his meticulously-chosen color palette, the rigorous symmetry of his framing, the obsessive detail of his visual design, and the almost cavalier irony of his tone. These now-familiar stylistic trappings give his movies the feel of a “junior-adventurer” story, belying the reality that the underlying tales he tells are quite grim. The cartoonish quirks of his characters often mask the fact that they are lonely or emotionally stunted – and the colorful, well-ordered world they inhabit is full of longing, hardship, oppression, and despair.

“Isle of Dogs,” though ostensibly a children’s movie, is no different. Indeed, it is possibly the director’s darkest work so far, and it is certainly his most political. Though it would be misleading to attribute a partisan agenda to this film, it’s not hard to see the allegorical leanings in its premise of a corrupt government demonizing dogs to incite hysteria and support its rise to power, nor the social commentary in the way it portrays bigotry based on the trivial surface characteristic of preferring dogs to cats. Make no mistake, despite its cute and fluffy surface and its future-Japanese setting, “Isle of Dogs” can easily be read as a depiction of a world possessed by the specter of Nationalism, and a clear statement about life – and resistance – in Trump’s America.

In terms of visual artistry, Anderson has outdone himself with his latest work. The painstaking perfection of the animation is matched by the overwhelming completeness of the world he and his design artists have executed around it. Myriad elements from Japanese culture are used to build the immersive reality of Megasaki (and Trash Island, of course), and the director adds to his own distinctive style by taking cues from countless cinematic influences – Western and Eastern alike.

Of course, the film’s setting and story invite comparisons to the great Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa – whose iconic Samurai movies were an acknowledged influence. Anderson mirrors the mythic, larger-than-life quality of those classics; he uses broad strokes, with characters who seem like archetypes and a presentation that feels like ritual.

These choices may have served the director’s artistic purpose well – but they have also opened him up to what has surely been unexpected criticism.

Many commentators have observed that, by setting “Isle of Dogs” in Japan (when he himself has admitted it could have taken place anywhere), Anderson is guilty of wholesale cultural appropriation, co-opting centuries of Japanese tradition and artistry to use essentially as background decoration for his movie. In addition, he has been criticized for his tone-deaf depiction of Japanese characters; his choice to have their dialogue spoken in (mostly) untranslated Japanese serves, it has been said, to de-humanize and marginalize them and shift all audience empathy to the English-speaking, decidedly Anglo actors who portray the dogs. There has also been objection to his inclusion of a female foreign exchange student as the leader of the resistance, which can be seen as a perpetuation of the the “white savior” myth.

Such points may be valid, particularly in a time when cultural sensitivity and positive representation are priorities within our social environment. It’s not the first time Anderson has been criticized for seeming to work from within a very white, entitled bubble, after all.

Even so, watching “Isle of Dogs,” it’s difficult to ignore the fact that it’s a movie about inclusion, not marginalization. It invites us to abandon ancient prejudices, speak up against institutionalized bigotry, and remake the world as a place where there is room for us all.

It’s a message that seems to speak to the progressive heart of diversity. Whether or not the delivery of that message comes in an appropriate form is a matter for individual viewers to decide for themselves.

For Anderson fans, it will probably be a moot point.