Today’s Cinema Adventure originally appeared in

There’s a comparatively high level of visibility for drag performers on the entertainment scene today. Not long ago, they were known only to the LGBT community and a few savvy “straights;” now, thanks to widening acceptance, you would be hard-pressed to find anyone not at least marginally aware of “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” or of movies like “Kinky Boots.” While still not exactly mainstream, drag has emerged from the gay bar and planted its cha-cha heels firmly on the stage of popular culture.

Most of the time, we are treated largely to the finished product of an artist’s long struggle towards triumphant self-expression. This is as it should be; drag deserves to be celebrated for its own merit. Still, it’s been decades since “Torch Song Trilogy,” and the time seems ripe for a new story about the offstage life of a queen. Thanks to film director Paddy Breathnach and screenwriter Mark O’Halloran, we need wait no longer.

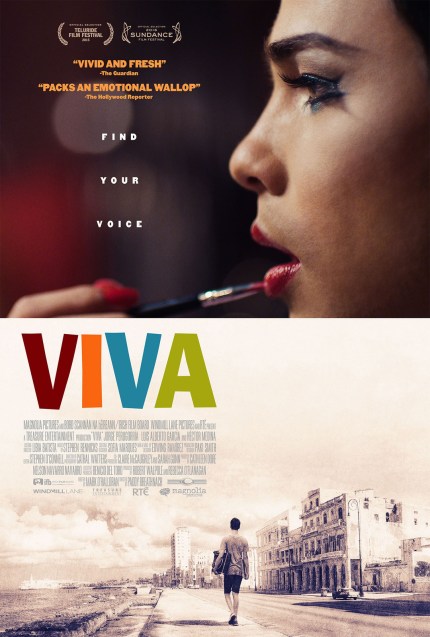

Set in the slums of Havana, “Viva” follows Jesus, a gay eighteen-year-old who supports himself by styling hair for his female relatives- and the wigs of the queens at a local drag club. Given a chance to perform himself, he is just beginning to blossom when his father Angel- a “local hero” boxer who abandoned him at the age of three- suddenly returns to his life. Angel- a homophobic macho man- insists on moving in with his son and refuses to allow him to continue working at the club. Torn between his longing for a father he never knew and his new-found self-expression, Jesus must forge a relationship with this stranger and attempt to build a bridge between their seemingly incompatible worlds.

From its very first scenes, “Viva” promises to be the story of an awkward gay boy’s evolution into a fabulous queen. It delivers on that promise, but not by taking the expected route. Though it starts us through familiar territory- the trying on of wigs and outfits, the catty dressing-room banter, the obligatory jokes about tucking- it suddenly (and literally) stops us in our tracks with a punch to the face. From that point forward, Jesus’ story is less about the outer trappings of drag and more about the inner journey that will eventually bring power and passion to his stage persona- and give him the strength and integrity necessary to live truly as himself.

We’ve seen the hard-knock, emotionally dysfunctional background of such a character before, of course, but in the past it has usually been portrayed as something to rise above, with drag as both protective armor and triumphal raiment. Here, though, Breathnach and O’Halloran give us a new take, in which their protagonist embraces his hardships instead of enduring them. It’s a subtle change of focus, underscoring a shift into a new era in which there’s a chance for those who don’t conform to societal “norms” to be true to themselves without having to live a life apart.

The key reason that “Viva” has resonance at a societal level is that O’Halloran’s script avoids politicizing or pontificating and instead focuses on an intimate relationship between father and son. In their negotiations, Jesus and Angel serve as stand-ins for their respective generations- and if these two men can gain acceptance from each other, there is hope for us all to do the same. Director Breathnach understands where the strength of his movie lies; other than making sure that the Havana location (described by Angel as “the most beautiful slum in the world”) is magnificently captured, he wisely keeps his cinematic styling simple and direct, allowing his cast to dominate the screen.

It helps that the actors- especially the movie’s two handsome co-stars- are up to the challenge. The movie naturally belongs to Héctor Medina; the young actor combines sensitivity and strength, his expressive face allowing us to experience Jesus’ journey with him, and caps it with a climactic performance in which he brings the film’s title character into a full, electric life of her own. As Angel, Jorge Perugorría embodies the hubris of culturally-bestowed entitlement, yet infuses his character with the humanity necessary to invite love and compassion. Providing an important third perspective to their dynamic is Luis Alberto García, who elegantly avoids stereotype as “Mama,” the drag club owner who takes Jesus under his wing.

Though it’s an Irish-made movie, “Viva” is spoken in the Spanish appropriate to its Cuban setting. This might be a challenge if you are subtitle-averse, but to skip seeing it would be a mistake for anyone who longs for world-class LGBT-themed cinema. By eschewing heavy-handed tactics, it takes a story which, in the not-too-distant past, might have been a tale of despair and tells it instead as parable of hope.