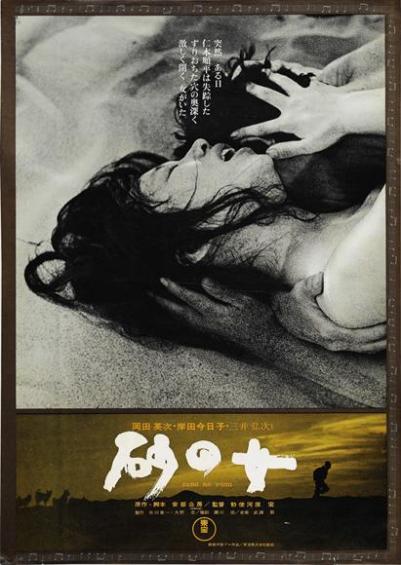

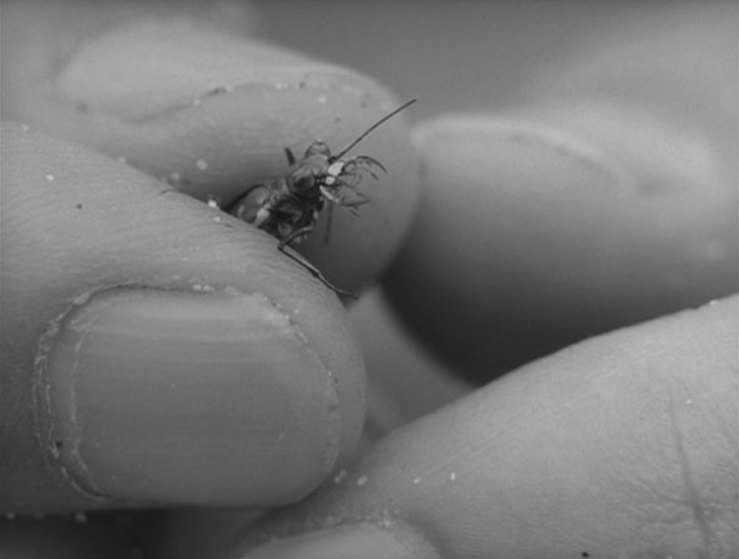

Today’s cinema adventure: Woman in the Dunes the strikingly photographed 1964 avant garde feature by Japanese filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara, Adapted by Kōbō Abe from his own novel, it’s a deceptively simple parable about an entomologist on a field expedition to collect specimens at a remote beach; when he misses his return bus, he seeks shelter for the night with a young widow in a local village- only to find himself trapped into remaining as her companion in a life of endless labor, shoveling sand from the quarry in which they live, both for their sustenance and to prevent their house from being buried. Within the framework of this premise are explored a multitude of giant, deeply reverberating themes, ranging from the contrast between the masculine and the feminine to man’s role in society to the very nature and meaning of existence itself- all of which plays out against the backdrop of the monumental, ever-shifting sand dunes, emphasizing the inexorable dominance of nature and the universe and transforming the primal landscape into a central character of the drama. The performances of the two principals (Eiji Okada and Kyoko Kishida) are superb, helping to create the delicate balance between realism and symbolic fantasy that propels the film- but the true star here is the magnificent black-and-white cinematography of Hiroshi Segawa, which not only captures the fluid, omnipresent sand in remarkable, crystalline detail, but conveys a sense of tangibility to every texture in the film, from the salty grit which covers every surface to the smoothness of the players’ skin, making the viewer’s experience highly visceral- and erotic. One of those world cinema classics that is a staple in film classrooms around the world, the artistry of Woman in the Dunes is indisputable- some audiences, however, may find that its blend of existential absurdism and Zen austerity creates a cool detachment that prevents emotional involvement in the action. Nevertheless, as an intellectual and philosophical exercise- and as piece of stunning visual artistry- it’s a film which packs more than enough power to make its 2 ½ hour running time seemingly fly by. A must-see for any serious film buff- but you may feel like you need a long shower to rinse off all that sand.

Category Archives: Surreal

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Today’s cinema adventure: The Man Who Fell to Earth, Nicholas Roeg’s 1976 feature starring David Bowie in his first leading film role. Based on a 1963 novel by Walter Tevis, it tells the story of Thomas Jerome Newton, an extra-terrestrial visitor who uses his advanced technology to build an enormous fortune, with the intention to finance the transport of water back to his drought-ravaged home planet, only to be trapped by the interference of corporate and governmental forces- and by his own indulgence in the pleasures of an earthly lifestyle. Visually arresting, leisurely paced, solemn and thoughtful in tone yet experimental and occasionally sensational in style, Roeg’s film (like it’s protagonist) is something of an enigma. Eschewing clarity for mood, the director obscures the storyline with surreal imagery depicting the visceral experiences of its characters, flashbacks to the blasted desert landscape of Newton’s world, strange episodes of temporal disturbance, and a continual shifting of focus among the perspectives of the various principals. The result is a disjointed, confusing film which seems designed to make sense only upon repeated viewings, with plot points revealed in passing by off-handed dialogue, the omission of key details which forces them to be filled in by audience assumption, and the ambiguous resolution of major story elements which leaves more questions than answers. These, however, are deliberate moves on Roeg’s part; he is less interested in presenting a cohesive science fiction narrative than in exploring a metaphor about the lure of wealth and pleasure and the corruptive influences of social and political forces, and he expresses these themes through a meticulously edited mix of hallucinogenic, serene, majestic and pedestrian images which blend to create a dreamlike final product. As for the acting, the key supporting roles are effectively filled by experienced pros Rip Torn and Buck Henry, as well as seventies flavor-of-the-day starlet Candy Clark as a blowsy hotel housekeeper who becomes Newton’s companion; but the film is, of course, centered on Bowie, here at the height of his rock icon popularity, who provides the perfect blend of childlike simplicity and jaded sophistication, exuding both poise and vulnerability and projecting the haunted longing and the bitter disillusionment that mark Newton’s odyssey through the experiences of our planet. Bowie himself has admitted to his heavy use of cocaine during the making of the film, which (though regrettable from many viewpoints) no doubt served to enhance the dissociated, alien persona which so perfectly complements its dreamy, distant mood. Added to the mix is superb cinematography by Anthony Richmond (which dazzlingly captures, among other things, the beauty of the New Mexico landscape that provides the setting for much of the film) and a well-chosen soundtrack of music (compiled by ex-Mamas-and-Papas-frontman John Phillips) featuring avant garde compositions and familiar pop tunes from various eras. The bottom line on this cult classic: if you are looking for a straightforward sci-fi tale, don’t look here- although the currently available version is a restored director’s cut which makes the plot somewhat more coherent than the highly-edited original release, you are almost guaranteed to be disappointed. However, if you are interested in a thought-provoking visual experience (or if you are a hardcore Bowie fan), this really is a must-see, and though it is ultimately somewhat cold and unsatisfying, it is a film which will stay with you for a long time afterwards.