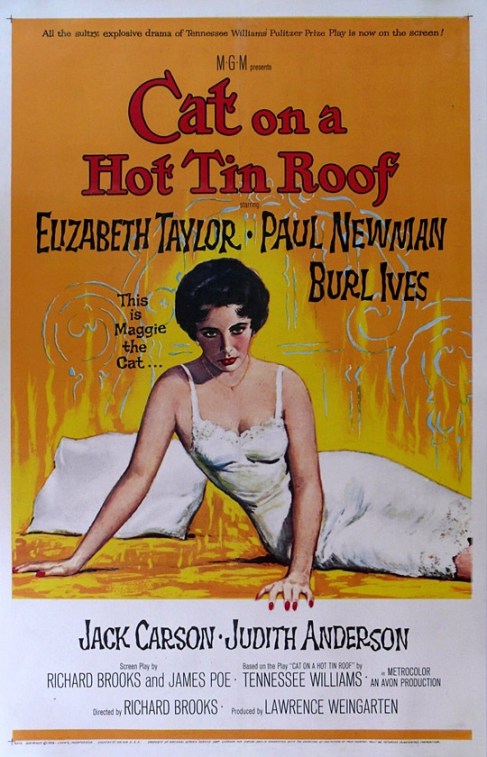

Today’s cinema adventure: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the 1958 screen adaptation of the Pulitzer-winning drama by playwright Tennessee Williams. Set on the plantation of “Big Daddy” Pollitt, a Southern cotton tycoon who has just been diagnosed with terminal cancer, the plot revolves around the angling of the patriarch’s family for control of his estate and the various conflicts between them, particularly between the heavy-drinking youngest son, Brick, and his wife, Maggie, whose relationship has gone cold over a recent tragedy- and a guilty secret. Produced at the height of the glamorous era of late-fifties American cinema, and starring two of Hollywood’s biggest stars of the time- Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman- it was an A-list prestige production and one of the ten biggest box office hits of the year, yet both Williams and leading man Newman expressed disappointment in the final product; indeed, the playwright publicly distanced himself from the film, even telling potential audiences to stay home. Their reticence, shared by numerous critics and literary purists, was due to the studio censorship, influenced by the then-still-observed Hays Code, which led to the removal of the play’s homosexual references- rendering the central conflict of between the two leads vague and unconvincing- and to the extensive rewriting of the final act to allow for a more “satisfying” reconciliation between Big Daddy and his alcoholic son. While it is certainly true that this filmed version of Williams’ personal favorite play was substantially tamed down from its original form, it nevertheless provided plenty of controversy in 1958: even without overt reference to homosexuality, savvy viewers could certainly still pick up on the unspoken truth behind Brick’s gnawing shame; and puritanical eyebrows were raised in abundance over the sexual frankness of the dialogue (not to mention the sultry chemistry between the stars, surely two of the most beautiful people ever to step in front of a camera). These controversial elements no doubt contributed greatly to the film’s popularity at the time; but by today’s standards, of course, its content would barely warrant a PG rating. What then, if anything, is there to recommend this venerable artifact of mid-century sophistication to modern audiences? To begin with, the sets, the costumes, the cinematography- the entire production- is everything you would expect of a high-budget, top-notch MGM product; but the same is true of many infinitely less watchable films from the same era. What really matters here is the material. Even watered-down Williams is a treat to see and hear, particularly in the hands of a cast capable of bringing out the rich, musical literacy and the deep, resonant emotional landscape of his text; and though director Richard Brooks (who also co-wrote the sanitized screenplay with James Poe) crafted a relatively uninspired film version, cinematically speaking- particularly when contrasted with other Williams adaptations of the time, such as the earlier classic, A Streetcar Named Desire– he clearly had a strong enough understanding of the piece to evoke uniformly superb performances from his players. Recreating his role from the Broadway production, Burl Ives dominates his every scene- and appropriately so- as Big Daddy, overbearing all before him with a grim, determined Southern smile even when most assaulted by pain, whether emotional or physical. Matched against him is the great Judith Anderson, oddly cast but highly effective as Big Mama, creating a sympathetic portrait of a woman, hardened but unbeaten by a lifetime under her husband’s imposing shadow, desperately clinging to the illusions she has worked to maintain for herself and her family. Jack Carson is likable as older brother Gooper despite the ineffectual disinterest of a character forever dominated by the others around him; and, as his wife Mae, Madeleine Sherwood (another veteran of the Broadway production) balances him by being equally dis-likable, an embodiment of mean-spirited pettiness, hypocrisy and self-righteous entitlement that serves as the closest thing in the piece to a villain. Of course, all this stellar supporting work would be meaningless without equally strong performances from the leads, and the two iconic stars here give performances that rank among the finest of their careers. As Brick, Newman proved once and for all that his ability as an actor was as formidable as his steely-blue-eyed good looks; he gives a remarkable and definitive interpretation of the character, playing against those leading-man-looks to bring out the ugliness of Brick’s dissolute bitterness- the high-handed and deliberate cruelty, the obstinate refusal to face his demons, the willfully self-destructive embrace of his alcoholism- without ever completely obscuring his underlying sensitivity and compassion, creating a complete portrait of a good man crippled (both literally and metaphorically) by the effects of failure, regret, and shame. The keystone performance, however, comes from Taylor, at the peak of her astonishing beauty and the beginning of her reign as one of Hollywood’s most glamorous and beloved stars. It would be easy to play Maggie “the Cat” as an ambitious, tawdry social climber bent only on claiming the family fortune of a man she has married for money, but Taylor makes her so much more: she not only radiates the aching sexuality of a woman too long neglected, but also the determination and candor which make it clear that she alone has the strength to be Big Daddy’s true successor as the dominant force in this family, coupled with the earnest feeling that makes it possible for us to believe, in the end, that she has the power to “make the lie true.” That, ultimately, is what Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is about: in a world full of “mendacity,” it takes passion and, yes, love to make the difference between truth and illusion. This first and still most authentic film version, with all its Technicolor gloss and its soundstage artificiality, is Hollywood illusion at its most persuasive- but thanks to Miss Taylor and the rest of its remarkable cast, it has the real ring of truth about it, and that is what makes it a classic.

Category Archives: Literary Adaptation

The Invisible Man (1933)

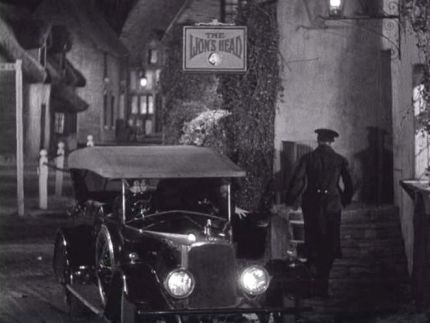

Today’s cinema adventure: The Invisible Man, the 1933 feature based on H.G. Wells’ story about a well-meaning scientist who discovers the secret of invisibility only to be driven to madness by its side-effects. Produced at the height of Universal Studios’ early-thirties cycle of horror films, it established a familiar screen icon in the form of its bandage-wrapped title character, and is still considered one of top classics of the “monster movie” genre. Its revered status is mostly due to director James Whale (the genius responsible for the first two Frankenstein movies), who combines a flair derived from his theatrical background with a keen cinematic style; his meticulously choreographed scenes are captured with inventive camera angles and expressionistic lighting, and his innovative techniques of visual storytelling- clever segues and montages, the savvy use of special effects to enhance his story rather than to dominate it- are a bittersweet testament to the brilliance that might have led to a long and remarkable filmmaking career had his distinctive artistic sensibilities not put him at odds with the Hollywood establishment and resulted in his early retirement from the industry. Those sensibilities are on full display here: his arch, campy style results in a film ripe with macabre humor, and one which feels decidedly subversive in its gleefully ironic portrayal of a stodgy community disrupted from within by willful anarchy. Nevertheless, despite a tone which could almost be described as self-mocking, the story never loses its dark undercurrent of unsettling horror- not the horror of violence and mayhem (though there is a fair share of that), but the horror of that unseen menace within the human psyche- the potential for corruption and dehumanization that can transform even the gentlest soul into a monster capable of unspeakable acts of cruelty. This balance between the wacky and the weird is achieved not only by the director’s considerable gift, but hinges also on a star-making performance in the title role by Claude Rains, who manages to walk the precarious line between histrionic mania and subtle sincerity, conveying perfectly the journey of a man struggling to hold onto himself even as he disappears into ego-driven insanity, and successfully holding audience sympathy even as he plots the most horrific acts of terror and revenge. It is a feat made even more remarkable by the fact that his face remains hidden until the final moments of the film, and which deservedly led to a career as one of Hollywood’s most prolific and well-loved character actors. The rest of the primary cast is effective enough, considering the prosaic acting styles of the era; notable more for their later accomplishments are Henry Travers (who went on to become everybody’s favorite guardian angel in It’s a Wonderful Life) and Gloria Stuart (who, 60 years later, became the oldest Oscar-nominated performer in history for her role in Titanic). Though most of the supporting players come off as merely adequate, however, the army of background actors are a delight- an array of craggy, comical English faces headed by the incomparable Una O’Connor as a shrill hostess whose encounter with the mysterious stranger at her inn sets the comically creepy tone for the entire film. R.C. Sheriff’s screenplay, though it features more than a little stodgy dialogue, captures the essence of Wells’ novel- particularly its allegorical exploration of the destructive effects of drug addiction- while expanding details of character and plot and building the foundation for Whale’s subtly skewed interpretation. The technical elements of the film are as top-notch as one would expect from a prestige production like this: the scenic design blends an art-deco flavor with the rich detail of its various English settings, the cinematography (by the great Arthur Edeson) is a sublime example of the near-forgotten beauty and power of black-and-white film, and the special effects (supervised by John Fulton), which were advanced for their time, are still fairly impressive for the most part. Of course, for today’s average audience, The Invisible Man may bear the stigma of being dated, creaky and far too tame for modern tastes; it may also suffer mildly from its abrupt and somewhat anti-climactic resolution. Even the most jaded viewers, however, will likely be drawn in by the considerable charm of a movie that inspires them to laugh out loud as they contemplate the deeper, darker themes which bubble within it like the test tubes in a mad scientist’s arcane lab.

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011)

Today’s cinema adventure: We Need to Talk About Kevin, the disturbing and controversial 2011 feature based on Lionel Shriver’s award-winning 2003 novel of the same name. Tilda Swinton stars as Eva, a woman haunted by memories and repercussions as she attempts to come to terms with the horrific acts committed by her teenaged son. As directed by BAFTA-winner Lynne Ramsay, the film draws us in from its very first moments with arresting visuals and an enigmatic soundscape, unfolding its nightmarish story through a non-sequential progression of scenes and images that gradually piece together like the shattered fragments of Eva’s life. It’s riveting stuff: Ramsay (who also co-wrote the screenplay with husband Rory Kinnear) keeps us engaged and unsettled throughout, saturating us with stylish imagery marked by an ingenious use of color (with a decided emphasis on red, maintaining an ever-present suggestion of blood), layering in just enough foreshadowing and clues to conjure a growing sense of dread over the inevitable conclusion, infusing each scene with an atmosphere of resigned melancholy and foreboding, and dominating the proceedings with an uneasy silence which is only broken by spare, terse dialogue that shocks and pierces as much as it informs. As we observe Eva’s disjointed recollections and her nightmarishly surreal day-to-day life, we find ourselves drawn into her psyche; forced to face the uncomfortable- and unanswerable- questions raised about the culpability of a parent in the wrongs committed by their offspring; and in the end, the biggest question may be how to find a resolution, a sense of closure which can permit the lives of those left standing to go on- and if, indeed, such a thing is even possible. With all these psychological themes in play, one might be tempted to consider We Need to Talk About Kevin to be a complex drama, but make no mistake about it: this is unquestionably a horror film, the kind of nightmarish thriller that is rarely made these days. It follows no pre-molded formula, and there are none of the expected clichés of the genre: no sudden shocks, no scantily-clad female victims screaming as they flee through the dark night, no oceans of gore (for all the red flowing across our eyes, there is very little blood or violence onscreen, with Ramsay opting instead to paint the horrible pictures in our imagination where they are infinitely more disturbing). This is not some schlocky shocker designed for a teenagers’ date night, but rather, like other great adult horror films of the past such as The Exorcist or Rosemary’s Baby, it is an exploration of evil in our lives, of how it manifests and what might be its causes; but unlike the aforementioned classics, there is no suggestion here of supernatural forces- the responsibility is placed squarely on human shoulders, with implications that are far more chilling than the presence of any demonic scapegoat. It would be easy, in the wrong hands, for Kevin to veer off into the realm of exploitative trash; but not only is Ramsay well-equipped for the task, she has the considerable benefit of Tilda Swinton in the central role. Swinton has proven many times that she is one of the most electrifying screen performers working today, and here she solidifies that reputation with a stunning, solid portrayal of a woman for whom the joy of motherhood has been inverted into a nightmare. With a minimum of dialogue, she conveys Eva’s harrowing journey with masterfully subtle changes in her continuous expression of dull shock, bringing home the frustration, the terror, and the loneliness created by the growing comprehension that her child is a monster and she alone can see it. It’s a tour-de-force performance, and its failure to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress- particularly when it was recognized by virtually every other major awards organization- was surely one of the great injustices of Oscar history. Supporting Swinton’s magnificence is John C. Reilly, likeable but obtuse as Eva’s husband, a man whose doting denial helps to enable the ever-escalating sociopathy of their son and drives an immovable wedge into their marriage; and a shining turn by Ezra Miller as the title character, who skillfully avoids the temptation of playing for sympathy- this is no misunderstood, angst-ridden adolescent, but a young cobra smugly and gleefully coiling up for a fatal strike. Mention is also deserved for Jasper Newell, as the six-to-eight year-old Kevin, who eerily projects a malicious menace beyond his years, somehow making the younger incarnation even more frightening than his future self. In addition to the stellar cast, Ramsay is aided in her vision by superb work from her technical collaborators: an eerie and atmospheric score by Johnny Greenwood (of Radiohead) meshes seamlessly with the carefully orchestrated sound design by Paul Davies; the cinematography by Seamus McGarvey provides some of the most vividly realized images in recent film memory, into which the simple-yet-striking costume design of Catherine George is brilliantly coordinated; and the editing by Joe Bini is a masterpiece of visual juggling, managing to maintain a steady flow throughout a narrative which freely jumps forward and back to multiple periods in time. It is a shame- but not a surprise- that We Need to Talk About Kevin has yet to recoup the $7 million that was spent to make it; you can chalk it up as yet another sign that the contemporary film market is driven by an increasingly less sophisticated mindset, but this would be a difficult film to sell in any era, really. It is a psychological thriller that dares to address deeply disturbing issues which most of us would prefer to keep out of sight and out of mind, and watching it is a grim and unrelenting experience which may leave you disturbed for days afterward. If that sounds as good to you as it does to me, We Need to Talk About Kevin is a film you must not miss.

Woman in the Dunes/Suna no onna (1964)

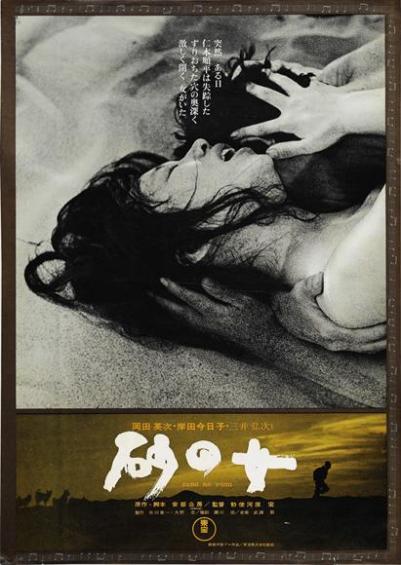

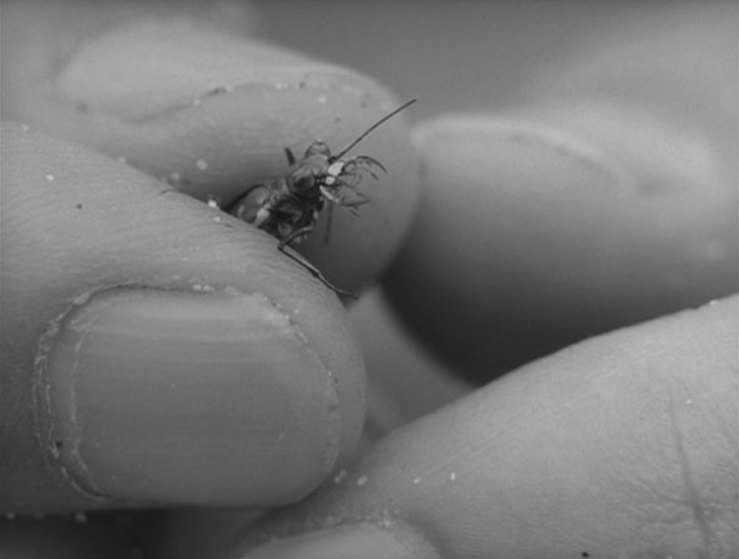

Today’s cinema adventure: Woman in the Dunes the strikingly photographed 1964 avant garde feature by Japanese filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara, Adapted by Kōbō Abe from his own novel, it’s a deceptively simple parable about an entomologist on a field expedition to collect specimens at a remote beach; when he misses his return bus, he seeks shelter for the night with a young widow in a local village- only to find himself trapped into remaining as her companion in a life of endless labor, shoveling sand from the quarry in which they live, both for their sustenance and to prevent their house from being buried. Within the framework of this premise are explored a multitude of giant, deeply reverberating themes, ranging from the contrast between the masculine and the feminine to man’s role in society to the very nature and meaning of existence itself- all of which plays out against the backdrop of the monumental, ever-shifting sand dunes, emphasizing the inexorable dominance of nature and the universe and transforming the primal landscape into a central character of the drama. The performances of the two principals (Eiji Okada and Kyoko Kishida) are superb, helping to create the delicate balance between realism and symbolic fantasy that propels the film- but the true star here is the magnificent black-and-white cinematography of Hiroshi Segawa, which not only captures the fluid, omnipresent sand in remarkable, crystalline detail, but conveys a sense of tangibility to every texture in the film, from the salty grit which covers every surface to the smoothness of the players’ skin, making the viewer’s experience highly visceral- and erotic. One of those world cinema classics that is a staple in film classrooms around the world, the artistry of Woman in the Dunes is indisputable- some audiences, however, may find that its blend of existential absurdism and Zen austerity creates a cool detachment that prevents emotional involvement in the action. Nevertheless, as an intellectual and philosophical exercise- and as piece of stunning visual artistry- it’s a film which packs more than enough power to make its 2 ½ hour running time seemingly fly by. A must-see for any serious film buff- but you may feel like you need a long shower to rinse off all that sand.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Today’s cinema adventure: The Man Who Fell to Earth, Nicholas Roeg’s 1976 feature starring David Bowie in his first leading film role. Based on a 1963 novel by Walter Tevis, it tells the story of Thomas Jerome Newton, an extra-terrestrial visitor who uses his advanced technology to build an enormous fortune, with the intention to finance the transport of water back to his drought-ravaged home planet, only to be trapped by the interference of corporate and governmental forces- and by his own indulgence in the pleasures of an earthly lifestyle. Visually arresting, leisurely paced, solemn and thoughtful in tone yet experimental and occasionally sensational in style, Roeg’s film (like it’s protagonist) is something of an enigma. Eschewing clarity for mood, the director obscures the storyline with surreal imagery depicting the visceral experiences of its characters, flashbacks to the blasted desert landscape of Newton’s world, strange episodes of temporal disturbance, and a continual shifting of focus among the perspectives of the various principals. The result is a disjointed, confusing film which seems designed to make sense only upon repeated viewings, with plot points revealed in passing by off-handed dialogue, the omission of key details which forces them to be filled in by audience assumption, and the ambiguous resolution of major story elements which leaves more questions than answers. These, however, are deliberate moves on Roeg’s part; he is less interested in presenting a cohesive science fiction narrative than in exploring a metaphor about the lure of wealth and pleasure and the corruptive influences of social and political forces, and he expresses these themes through a meticulously edited mix of hallucinogenic, serene, majestic and pedestrian images which blend to create a dreamlike final product. As for the acting, the key supporting roles are effectively filled by experienced pros Rip Torn and Buck Henry, as well as seventies flavor-of-the-day starlet Candy Clark as a blowsy hotel housekeeper who becomes Newton’s companion; but the film is, of course, centered on Bowie, here at the height of his rock icon popularity, who provides the perfect blend of childlike simplicity and jaded sophistication, exuding both poise and vulnerability and projecting the haunted longing and the bitter disillusionment that mark Newton’s odyssey through the experiences of our planet. Bowie himself has admitted to his heavy use of cocaine during the making of the film, which (though regrettable from many viewpoints) no doubt served to enhance the dissociated, alien persona which so perfectly complements its dreamy, distant mood. Added to the mix is superb cinematography by Anthony Richmond (which dazzlingly captures, among other things, the beauty of the New Mexico landscape that provides the setting for much of the film) and a well-chosen soundtrack of music (compiled by ex-Mamas-and-Papas-frontman John Phillips) featuring avant garde compositions and familiar pop tunes from various eras. The bottom line on this cult classic: if you are looking for a straightforward sci-fi tale, don’t look here- although the currently available version is a restored director’s cut which makes the plot somewhat more coherent than the highly-edited original release, you are almost guaranteed to be disappointed. However, if you are interested in a thought-provoking visual experience (or if you are a hardcore Bowie fan), this really is a must-see, and though it is ultimately somewhat cold and unsatisfying, it is a film which will stay with you for a long time afterwards.