Today’s cinema adventure: My Week With Marilyn, the wistful 2011 biopic based on Colin Clark’s memoir, The Prince, the Showgirl, and Me, which detailed the author’s brief relationship with iconic starlet Marilyn Monroe during the turbulent filming of The Prince and the Showgirl with actor/director Sir Laurence Olivier. Whereas many film biographies attempt to shed light on their subjects by presenting their life in its entirety, this charming true-life romance focuses instead on a short episode, using it as prism to cast insight into the legendary actress and her contemporaries. As a result, the film has an intimacy and an authenticity lacking in most Hollywood bios, and the narrowing of focus allows the performers to explore the nuances of their real-life characters with much greater depth and detail, heightening the illusion that we are watching real people instead of the larger-than-life caricatures to which we are so often subjected. Those performers, without exception, rise to the occasion: the entire ensemble clearly relishes its chance to embody this slice of mid-century mythology. The much-lauded Michelle Williams is largely successful in capturing the enigmatic persona that made Marilyn the biggest star in the world; she gives us the contrasting blend of sensuality and insecurity we expect but infuses it with a humanity that allows us to perceive the underlying causes of her fragility and need for validation, as well as the irresistible charm that won the hearts of so many. To be sure, her transformation is less than total- her physical attributes are not quite right, and her bearing sometimes seems mote timid than self-assured- but, of course, she is ultimately an actress interpreting a role, not a reincarnation, and as such she deserves much praise for conveying the essence of an oft-imitated woman who was, in fact, inimitable. Less glamorous, but perhaps even more impressive, is Kenneth Branagh’s work as Olivier which likewise captures the great actor’s outward persona with remarkable accuracy while showing the inner landscape of a man struggling to keep his place at the top in the face of changing standards in the art he has mastered for so long; Olivier was not only an early mentor for Branagh but an actor with whom his own career has often been compared, so he seems well-suited to the daunting task of personifying the legendary thespian- a task which he clearly relishes, recreating Olivier’s physicality and vocal patterns with intimate familiarity with0ut resorting to out-and-out mimicry, and treating his subject with obvious respect even when portraying some of his less attractive facets. As these two enact their clash of titans, they are surrounded by a host of worthy supporting performances, including Julia Ormond’s brief but canny portrayal of Vivien Leigh, Emma Watson’s decidedly non-Hermoine-esque turn as a wardrobe girl, and the always magisterial Dame Judi Dench as the always magisterial Dame Sybil Thorndike; but special praise should be reserved for Eddie Redmayne, who, stuck with the potentially thankless role of providing a foil for his co-stars, manages also to provide a solid ground for the proceedings by giving a quietly convincing performance as the young film crewman coming of age in the shadow of giants, and never lets us quite forget that this is, after all, his story. With all this great acting going on, it’s easy to overlook the film’s other pleasures- the meticulous costume and scene design; the rich, golden-hued cinematography by Ben Smithard; the understated archness of the screenplay by Adrian Hodges- all overseen by the steady hand of first-time director Simon Curtis, whose wise approach here is to step back and let all these elements leave their marks without the unnecessary assistance of showy cinematic trickery. The end result is a movie which, like the famous figure at its center, is lovely, effervescent, and hauntingly sad. It does not promise nor does it try to present the final word on Marilyn- or Olivier, for that matter- and for that very reason, probably comes closer to giving us a truthful, fair vision of these two legends than any scandal-raking exposé could hope to deliver.

Microcosmos: le peuple de l’herbe (1996)

Today’s cinema adventure: Microcosmos: le peuple de l’herbe (the grass people), a 1996 French documentary depicting the behavior and interaction of various insects and other minuscule creatures as recorded with specially-developed cameras and microphones that reveal their tiny world in a staggering and beautiful wealth of detail. Fifteen years in the making and originally shown on French television, it was marketed in the U.S. as a family-friendly nature film and became a relative hit at the box office- for easily understandable reasons. With remarkable cinematography that rivals today’s high-def technology in clarity and depth, directors Claude Nuridsany and Marie Pérennou construct a riveting chronicle of the world under our feet, accomplishing the improbable effect of inspiring empathy with the kinds of animals that, for most, normally inspire nothing but revulsion. Spiders, snails, mantises, ants, bees, earthworms, dung beetles and water bugs enact their daily experiences, and the titanic nature of their struggles is made visceral by the scale in which they are shown; the audience, transported into their tiny realm, is given a bug’s eye view of what it takes to survive, as well as being treated to some breathtaking footage of nature’s beauty, all to the accompaniment of a haunting score by film composer Bruno Coulais. Even more remarkable is that, with a bare minimum of narration (provided in the English-language version by Kristen Scott-Thomas), the audience is treated to drama, suspense, and even humor, arising naturally from the behavior of the film’s multi-legged cast; the overall result is a film experience that is not only educational, but entertaining, awe-inspiring, and, somehow, strangely moving.

Sebastiane (1976) [Warning: some images may be NSFW]

Today’s cinema adventure: Derek Jarman’s 1976 debut feature, Sebastiane, a fictionalized vision of the martyrdom of St. Sebastian, presented less as a meditation on spiritual themes than as a homoerotic fantasy in which the soldier Sebastianus, after falling from favor with the Roman Emperor Diocletian, is exiled to a remote oupost in the wilderness, where his refusal to yield to his commanding officer’s obsessive lust eventually leads to his ritual execution by arrows. A work that is historically significant not only for being the first film produced in authentic Latin (and as such, the first British-made movie to be shown in England with subtitles), but- more importantly- for the prologue featuring an erotic dance by legendary glam-era performance artist Lindsay Kemp and his Troupe, and its inclusion of an early score by electronic music pioneer Brian Eno, Sebastiane was never anybody’s idea of a mainstream film, not even its creator’s. Like most of Jarman’s films, it’s not big on story, but despite its shoestring budget, it is lovingly and beautifully shot, each frame artfully crafted so that the final result resembles a Renaissance painting in motion. The extensive nudity (all male, of course) was explained by Jarman as being because they “couldn’t afford costumes” (sure, Derek, sure… we believe you), and needless to say the film was highly controversial at the time of release; but although many viewers may fixate on what often seems like gratuitous nudity and sexual content, Jarman is not merely concerned with exploiting or even celebrating the male form; he has much to say about the issue of homosexual shame. On the surface, the film would seem to comply with the traditional Catholic assertion that homosexual behavior is a sin to be forsworn, and that Sebastianus’ fate is to be sacrificed to that ideal, destroyed by unrepentant sinners for his refusal to debase himself- a decidedly conflicting message, when one considers the fact that the film is heavily laden with imagery clearly intended to elicit homosexual fantasies. Certainly these themes of religiously-fueled guilt are in play within Sebastiane, and Jarman undoubtedly wrapped some of his own spiritual struggles into his film; but like most art, the true nature of the themes expressed lies beneath the obvious details. Sebastianus’ rejection is of the flesh itself, regardless of sexual orientation: it is his devotion to a life of the spirit that makes him an outcast and a martyr, and it is the jealousy and pride of those who fail to understand him that leads to his death; in the end, sexuality is irrelevant here, and Jarman’s true indictment is against the base and brutal tendencies of stereotypical masculinity, the hypocrisy of judgement and violence against those who do not conform to the status quo, and the arrogance of those who choose to subvert their own spirituality to their egotistical desires and insecurities. In short, the film is more about homophobia than homosexuality, and its abundance of homoerotic imagery is as much to incite as to excite. Of course, that same imagery is sufficient to ensure that the majority of religious bigots will never see this film, so in a way, Sebastiane is a prime example of an artist “preaching to the choir;” and, truthfully, the copious amount of it ultimately displaces Jarman’s higher purpose, so that his inaugural cinematic excursion ends up being more stimulating on a decidedly lower level. My own reaction: it’s a very pretty movie to look at, and probably one of the most erotic ones I have seen (much more so than porn, actually); but at times I couldn’t help being reminded of those soft-core late-night “Skinemax” flicks I would sometimes catch my Dad watching at 3 in the morning… slow motion photography of someone taking a shower, with the frame cropped in just the right place to keep it from being obscene, that sort of thing, except instead of beautiful women, here it was beautiful men. I can’t say I had any complaints, but I was ready for it to be over about 30 minutes before it actually was. It might have helped if the actors (Leonardo Treviglio as Sebastianus, supported by Barney James, Neil Kennedy, and Richard Warwick, among others- none of whom had significant careers afterward) had delivered performances that were as beautiful as their bodies… but I guess we can’t have everything.

Death Proof (2007)

Today’s cinema adventure: Death Proof, writer/director Quentin Tarantino’s 2007 homage to the cheap exploitation movies of the sixties and seventies, originally released as half of the Grindhouse double feature (paired with Richard Rodriguez’ Planet Terror). With his trademark style on full display, Tarantino sets out to emulate- and surpass- the violent and titillating “anti-classics” he clearly loves with this tale of a psychopathic ex-stunt driver who stalks and kills young women in his souped-up, “death-proofed” muscle car. Though Kurt Russell delivers a delightful performance in the central role, and the director’s impressive visual style is as dazzling as ever, the film is ultimately sabotaged by several factors. First of all, with its conceit of recreating the genre which inspired it, Death Proof severely impairs its own ability to engage the viewer in its proceedings: the deliberately grainy cinematography, scratched film and bad splicing constantly serve as a reminder that it’s all just an elaborate gimmick; the inherently shallow formula prevents the far-fetched and sensationalistic plotline from ever becoming believable or compelling; and the characters, for all the self-consciously clever dialogue Tarantino puts in their mouths, are doomed to remain one-dimensional ciphers who exist merely to enact the filmmaker’s cars-sex-drugs-and-rock-n-roll fantasy. All these criticisms, of course, could easily serve as a description of any of the B-movies upon which Tarantino’s opus is based; and it would be correct to point out that what really matters in those films (and in this one) is the nail-biting, balls-to-the-wall action and the gratuitous violence for which everything else simply provides a framework. But where the original films managed, at their visceral best, to thrill and delight, transcending their shoddiness with their lack of pretense and their unapologetic devotion to providing guilty pleasure, Tarantino’s would-be tribute fails to achieve any of these ends. To be sure, his talent is clearly visible here: but that’s part of the problem, for where the drive-in fodder he emulates was often so bad it was good, here we have an obviously good filmmaker deliberately trying to be bad, and succeeding in just being, well, bad; and though the action sequences- two of them, to be exact- are unquestionably well-done, in order to get to them (thanks to Tarantino’s self-indulgent insistence on maintaining his own signature tension-building style) we have to sit through interminable stretches of hip, foul-mouthed dialogue, which may be meant to invest us in the characters but instead results in repeated glancing at our watches. Seriously, there was never this much talking in Death Race 2000. Don’t get me wrong- I’m not criticizing Tarantino for embracing and championing the grindhouse genre. After all, these humble movies are touchstones for a generation and have had a major influence on contemporary cinema; and in his best work (such as the Kill Bill movies and Inglorious Basterds), the director has masterfully drawn inspiration from them while incorporating their elements into his larger personal vision. With Death Proof, however, he has only succeeded in making a pale shadow of the original works, which, like a replica of some crude masterpiece of outsider art, seems pointless and unnecessary.

Six Degrees of Separation (1993)

Today’s cinema adventure: Six Degrees of Separation, the 1993 adaptation of John Guare’s Pulitzer-nominated play of the same name, starring Stockard Channing, Donald Sutherland and Will Smith, with a screenplay by the playwright himself. Through the tale of a well-to-do Manhattan couple whose lives are infiltrated by a mysterious and charismatic young con artist, Guare uses his gift for language to explore how our connections to other people weave us into a tapestry of shared experience and lead us to new perspectives on our lives and ourselves, and to subtly reveal how the parallels between us transcend the illusory differences of class, race, sexuality and culture and expose the sometimes uncomfortable truths which unite us all; however, in the translation from stage to film, the complex, literate and emotionally resonant dialogue sometimes borders on sounding awkward and stilted, the central premise comes across as contrived and unconvincing, and the powerful revelations of the play seem almost artificial and trite. The fault lies with director Fred Schepisi, who- instead of utilizing the potential of the cinematic medium to enhance and illuminate the play- has taken the rather pedestrian approach of grafting it into a straightforward narrative, expanding the action into a variety of real-world settings which only serve to distance us from the characters and undermine the cumulative power of the unfolding story. The endless progression of upper-crust social gatherings and well-appointed locations continually remind us that we are watching a movie about the problems of spoiled rich people, instead of providing us with the class-dissolving intimacy of a more abstract theatrical experience; and as a result, instead of an emotional catharsis, we are given an intellectual exercise. Nevertheless, the power of Guare’s original work shines through (albeit in diluted form) thanks to the talented ensemble cast, which clearly relishes the opportunity to speak his words and embody his characters, and if the movie is ultimately a bit disappointing, they at least ensure that it is never boring. Sutherland is, as always, interesting to watch, and Channing does possibly her best screen work here- she earned a well- deserved Oscar nomination for her performance; Ian McKellen shines as wealthy dinner guest who is also taken in by the young hustler, as do Heather Graham and Eric Thal as a younger, less affluent couple whose experience with him yields considerably more tragic results. In the key role of the enigmatic stranger, Will Smith copiously displays the charm that made him a star; but my favorite performance comes from Anthony Michael Hall, whose brief appearance as a key character steals the show and makes us keenly regret his relative disappearance from the film industry. As a side note, from the standpoint of social history, Six Degrees represents a minor landmark in the acceptance of gay-themed subject matter in mainstream cinema with its inclusion of the con man’s homosexual trysts, which may generate interest for some viewers; for everyone else, however, it’s a film that is worth the time investment, for the sake of the performances and the opportunity to experience Guare’s script- just manage your expectations, or you may end up feeling you are the one who’s been conned.

Eating Raoul (1982)

Today’s cinema adventure: Eating Raoul, the dark 1982 low-budget satire which became a surprise hit and helped to start a wave of goofy “camp” comedies that pervaded the rest of the decade. Director/co-writer Paul Bartel, an exploitation cinema veteran, also stars with longtime friend and frequent co-star Mary Woronov as a married pair of sexual squares who lure “swingers” to their Hollywood apartment and kill them with a frying pan in order to finance their dream of opening a restaurant. Macabre as the premise seems- and in spite of a plot which features such elements as rape, serial murder and cannibalism- the film is kept light and fun by a healthy dose of good-natured kitsch and by its ridiculously over-the-top portrayal of the lurid “swinger” culture and its sexually liberated denizens. Bartel and Richard Blackburn’s screenplay is loaded with pseudo-shocking dialogue which exploits the ridiculousness of both prudish repression and extreme sexuality, peppered with great deadpan one-liners, and thematically unified by an exploration of the depravity hiding just under even the most respectable-seeming surfaces. Clever writing aside, the primary factor in the film’s success is the charm of its leading players: Bartel is somehow likeable and endearing despite his pompously indignant and über-nerdy persona; former Warhol “superstar” Woronov is a complex confection, undercutting her character’s uptight austerity with smoldering sensuality and a girlish vulnerability; and the chemistry between these oddball stars is palpable- they are clearly driven by the same skewed vision. Rounding out the main cast is Robert Beltran, equally charming and sympathetic as Raoul, the hot-blooded Latino hoodlum who attempts to blackmail and come between the couple- and whose ultimate fate is foreshadowed by the tongue-in-cheek title of the film. In addition, there are some delightful cameos by comedic masters such as Buck Henry, Ed Begley, Jr., and the incomparable Edie McClurg. The sordid proceedings play out against a now-nostalgic backdrop of seedy Los Angeles locations, accompanied by a quirky and eclectic soundtrack and driven at a brisk pace by Bartel’s quietly masterful direction. Don’t get me wrong here- Eating Raoul is by no means a masterpiece, even in the world of underground cinema- it lacks the anarchic, subversive edginess of a John Waters film, and its “shocks” are pretty tame, even by 1982 standards- but it is nevertheless a delight to watch, perhaps because for all its satirical snarkiness and its unsavory subject matter, there is an unmistakable sweetness at the center of its black little heart.

Prometheus (2012)

Today’s cinema adventure: Prometheus, the 2012 sci-fi thriller that marks the return of director Ridley Scott both to the genre and to the film franchise that made his name. A prequel of sorts to his 1979 classic, Alien, it follows the fate of a late-twenty-first-century space expedition which journeys to a distant planet in search of answers to the secret of human origin, revealing (partially) the background of the terrifying race of creatures that inhabited the earlier film and its sequels- but also establishing its own internal mythology, with a plot and a purpose completely independent of its predecessor, and tackling deeper, far-reaching philosophical themes along the way. Indeed, director Scott makes it clear from the very first frames that he has greater ambitions than just making a straightforward science fiction adventure: the opening shot is a direct copy of the one used by Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey– in fact, the entire credits sequence is reminiscent of an important scene from 2001, and throughout Prometheus there are countless echoes- some huge, some tiny- from that venerable masterpiece. This is appropriate enough, given that Scott’s film shares many of the central themes from Kubrick’s landmark opus, such as man’s continuing quest for knowledge and his uneasy relationship with the technology he has created to aid him in that quest; indeed, the central plot (the discovery of artifacts from earth’s ancient past leads to a space mission and a confrontation with the mysteries of our creation) is essentially the same in both films. Scott, however, working from the screenplay by John Spaihts and Lost co-creator Damon Lindelof, offers his own interpretation of these ideas; his is a much darker vision of our species and its place in the universe, and one which reflects the change in our collective consciousness in the 45 years since Kubrick made his film. In place of Kubrick’s somewhat ironic vision of a future shaped by nuclear age optimism and practicality, we are given a universe more closely resembling the one seen in Scott’s earlier visits to this genre: a place in which human flaws such as ego, greed, hostility, mistrust and duplicity run rampant; and where these qualities not only threaten to undermine the greater purpose but are seen to be shared by the very creative forces that shaped us. Not that Scott gives us a universe without hope- far from it. In Prometheus, hope is arguably the central issue, and holding onto it in the face of bleak nihilism can be seen as the one saving grace of our species- coupled with undying curiosity and armed with the knowledge of what has come before, it can keep us going even when there seems no purpose for doing so. In a way, Prometheus offers us an even more inspiring conclusion than 2001, suggesting that the secret of man’s creation and continuing renewal lies within ourselves, alongside the very seeds of our own destruction- no matter what our origins may be, we are self-determining creatures and not just pawns observing a cosmic waltz in which we may be a mere side effect.

All this conjuring of the spirit of 2001 may be justified by the needs of Scott’s intellectual premise, but it also serves as a means to pay homage to his cinematic influences; the visual and thematic reflections of Kubrick’s film are just the most obvious of his tributes to the works of those who have shaped his own vision, from the overt use of Lawrence of Arabia as an inspiration for one of the central characters to the more subtle nods in the direction of such diverse movies as Citizen Kane and Forbidden Planet. With such a pedigree, it would be nice to say that Prometheus is a worthy successor to the masterworks tagged within it; but despite its lofty goals, it is a film which suffers from the all-too-common malady of formula. The cinematic building blocks so reverently placed by Scott seem to promise a work of intelligence and depth- which, for the most part, he has given us- but as the plot unfolds towards its predictably cataclysmic conclusion, his movie falls into the familiar repetition of patterns we have seen ad infinitum: the characters’ fates can be foreseen from their virtues or flaws in the same way we can tell that the bad girls are going to get offed in a slasher film, pivotal plot elements are introduced with so many red flags we can instantly see where they will lead, and, of course, anyone familiar with the original Alien and its sequels will know from the outset where the story is headed, reducing the entire experience to a detached exercise in answering questions left over from the previous franchise entries. In addition, the level of tension, so expertly built and maintained by Scott in his original film, is here allowed to rise and fall so often and with so little payoff, that by the end we are not so much excited as we are mildly curious to see how things will finally play out. Furthermore, the insistence on maintaining a rigid connection to the concrete realism dictated by its cookie-cutter storyline prohibits the director from diverging from his linear plot into the absract flights of fancy that made 2001 such a groundbreaking work and prevents him from taking his cosmic themes into an esoteric realm where they can be more fully explored.

Don’t get me wrong: by any standards, Prometheus is a well-above-average film, an ambitious labor of love by a director of considerable talent; considering that its development and production history reads like an indictment of all that is wrong with the Hollywood process today, the fact that it offers so much substance along with its profit-minded formulaic plot is a miracle in itself. Scott has always been a director with remarkable gifts, particularly in visual terms, and this film certainly lives up to his reputation; it combines the immediacy of Alien with the elegiac reflection of Blade Runner; and, like both those examples, creates a stunning, immersive world for us to experience. Superbly photographed in 3-D by Dariusz Wolski, Prometheus presents a brilliant blend of its own shrewdly futuristic design and the H.R. Giger-inspired bio-technical look of the original Alien; and, to draw another comparison with 2001, it sets a new standard for special effects, with a look and a feel derived from dedication to the artistic purpose of the whole, not merely from a desire to dazzle us. This accomplishment is achieved, under the supervision of production designer Arthur Max, by a seamless blend of CG, traditional camera trickery, and live action footage, and it yields countless examples of big screen imagery which are surely destined to become iconic. All this technical wizardry is not wasted, notwithstanding the quibbles which mar the film’s narrative: Scott rises to the occasion throughout, creating moments of breathtaking beauty and visceral terror- in fact, the film’s most effective scenes (particularly a medically-themed sequence near the climax) are those which resurrect the creepy, primal body-horror around which the original was based and the fear of which is never far from our minds from the moment the exploration team lands. Aiding him in his struggle to rise above his mundane material is a fine cast which includes superb work from Charlize Theron (proving once again that she is Hollywood’s reigning ice queen), Idris Elba and Guy Pearce; standing out above the rest is the hypnotic Michael Fassbender, who provides further evidence of his substantial talent as the film’s most memorable and enigmatic character; and in the central role, Noomi Rapace makes a convincing transition from idealistic scientist to determined survivor, stirring favorable comparative memories of the franchise’s original heroine, Sigourney Weaver. The one sour performance comes from Logan Marshall-Green, whose hot-shot demeanor and club-rat looks make him not only unconvincing as a world-class scientist but also unlikable as a hero and poorly matched with Rapace’s much more sympathetic personality.

Prometheus has been anticipated as one of the year’s biggest film events, with much hype and secrecy surrounding its content and high expectations for both critical and commercial success. With all that pressure, it is not surprising that it has met, so far, with mixed reaction: hardcore fans of the genre have expressed disappointment with its emphasis on esoteric elements instead of on providing concrete answers to the mysteries it presents- many of which are left unrevealed, begging the development of a sequel despite the insistence of its makers that it is meant to be a stand-alone project- and serious-minded filmgoers have complained (as I did) of the reliance on cliché and formula in a plot which keeps it from fully realizing its higher goals. In the long term, who can really say where it will stand in the estimation of future cinemaphiles? What is certain now is that audiences seem to love it or hate it, which for me has always been the surest sign of artistic success. Summing up my own opinion, I would have to say that I loved it- with reservations. I can’t guarantee that you will share that view, but I can tell you that it’s worth a trip to your local theater to find out for yourself. You may not be satisfied, but you will almost certainly be stimulated and provoked, and isn’t that what art- and cinema in particular- is all about?

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1446714/

;

Chris and Don: A Love Story (2007)

Today’s cinema adventure: Chris and Don: A Love Story, a 2007 documentary detailing the 34-year relationship between acclaimed writer Christopher Isherwood and his life partner, artist Don Bachardy. Practicing documentary filmmaking at its finest, directors Tina Mascara and Guido Santi piece together the remarkable shared life of the couple while also presenting a portrait of each man individually, utilizing footage and narration from surviving partner Bachardy, excerpts from Isherwood’s diaries (read, appropriately enough, by Michael York, who portrayed the author’s alter-ego in the film version of the musical Cabaret, based on Isherwood’s Berlin Stories), interviews with various friends and archivists, and copious home movies and photographs of the couple’s life together. The relationship, which began when the 48-year old British expatriate author met the 18-year old Los Angeles boy on a beach in Santa Monica and defied the odds- and the cynical expectations of the pair’s acquaintances- to endure until Isherwood’s death in 1986, is presented with a restraint and an objective journalistic detachment which preserves the dignity of its subject matter and results in a cumulative emotional wallop, leaving the viewer moved and uplifted by the triumph of an unlikely love. Documentary purists may quibble over the occasional use of re-enactments to depict key moments in the relationship (presented only in brief, out-of-focus snippets without dialogue) and animations derived from Isherwood’s fanciful sketches from his correspondence to his partner, but these touches do nothing to alter or affect the facts presented. Though the film depicts the lives of a gay couple, it is suitable for all audiences; and anyone who watches it is bound to be, as I was, filled with admiration for two people who disregarded social prejudices from every direction and inspired by their success at building a love to last a lifetime.

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Today’s cinema adventure: Dog Day Afternoon, the 1975 Sidney Lumet feature about a real-life bank heist gone wrong, in which a troubled Vietnam war veteran attempts to obtain the money needed for his gay lover’s sex change surgery and ends up at the center of a hostage situation that turns into a media circus. A prime example of seventies “New Hollywood” cinema, this gripping gem achieved much popularity due to its anti-establishment undertones and the performance of Al Pacino, who was at the height of his rising stardom. Director Lumet, also at the peak of his career, steadily drives the brilliant Frank Pierson screenplay by allowing the story to unfold through the characters, resulting in a slow-but-steady paced film that remains emotionally grounded as it moves through the escalating complications of the plot, building tension by keeping us invested as it moves towards its inexorable conclusion; in addition, by focusing on the immediacy of the human element, Lumet succeeds in creating a microcosmic fable with complex political and social overtones woven into its fabric without ever letting these larger themes overwhelm the immediacy and intimacy of its simple story. The power of the film as a whole is seamlessly connected to the magnificence of Pacino’s embodiment of the likable loser at its center; his sharply honest portrayal allows us to instantly connect with the core of his character as he wavers between gullibility and cynicism, despair and determination, kindness and cruelty- seemingly the entire contrasting myriad of human emotion. It’s hard not to be on his side, no matter how ill-advised his actions may be; we share his giddy thrill when he stirs the crowd with his chants of “Attica!,” and we feel the crushing pressure as he tries to negotiate an acceptable way out of the no-win situation he is in- both in the bank and in his life. Backing him up is a quietly brilliant cast of supporting players, from John Cazale as his slow-witted accomplice and Charles Durning as the police negotiator trying to diffuse the situation, to the ensemble of bank-employees-turned-hostages who convincingly bond with their unwilling captor. Special praise, however, should go to Chris Sarandon, as Pacino’s gender-swapping lover, who delivers his two scenes with a sensitivity and a dignity that provide the bittersweet heart upon which the entire plot hinges. It is worth mentioning, in fact, that the homosexual elements of the film are handled with objectivity and a marked lack of stereotyping- a fact made all the more remarkable by the era in which it was made, which helps to make it stand as strong today as it did upon its first release nearly forty years ago. (As a side note, it is interesting to know that the film’s real-life inspiration, John Wojtowicz, used his proceeds from the sale of his story to finally fund his lover’s sex change; so in a roundabout way, his scheme ended up being successful after all). All in all, Dog Day Afternoon is one of those classics that define an era, a representative work from a time when American cinema blended realism with art to create a kind of visual poetry, a document testifying to the character of our culture and capturing the essence of our concerns. Not only that, it is a reminder of a time when Hollywood gave us stories that grew out of the people in them instead of relying on gimmicky, formulaic plots with the people grafted in- and though I’m not one to bemoan the passing of the “good old days,” it’s certain that today filmmaking establishment would be completely unable- or at least unwilling- to create a film with the kind of simple, non-CG-powered thrills provided here. Of course, you don’t need all these justifications for checking it out. The only reason you need is the best reason of all: it’s a damn good movie.

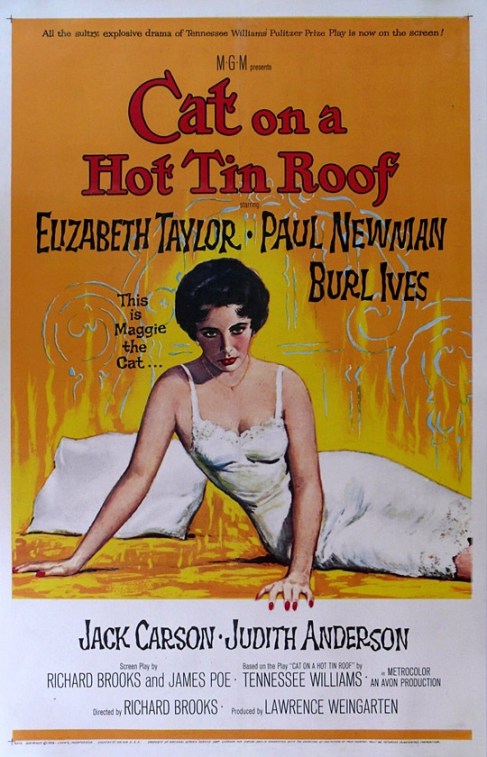

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

Today’s cinema adventure: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the 1958 screen adaptation of the Pulitzer-winning drama by playwright Tennessee Williams. Set on the plantation of “Big Daddy” Pollitt, a Southern cotton tycoon who has just been diagnosed with terminal cancer, the plot revolves around the angling of the patriarch’s family for control of his estate and the various conflicts between them, particularly between the heavy-drinking youngest son, Brick, and his wife, Maggie, whose relationship has gone cold over a recent tragedy- and a guilty secret. Produced at the height of the glamorous era of late-fifties American cinema, and starring two of Hollywood’s biggest stars of the time- Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman- it was an A-list prestige production and one of the ten biggest box office hits of the year, yet both Williams and leading man Newman expressed disappointment in the final product; indeed, the playwright publicly distanced himself from the film, even telling potential audiences to stay home. Their reticence, shared by numerous critics and literary purists, was due to the studio censorship, influenced by the then-still-observed Hays Code, which led to the removal of the play’s homosexual references- rendering the central conflict of between the two leads vague and unconvincing- and to the extensive rewriting of the final act to allow for a more “satisfying” reconciliation between Big Daddy and his alcoholic son. While it is certainly true that this filmed version of Williams’ personal favorite play was substantially tamed down from its original form, it nevertheless provided plenty of controversy in 1958: even without overt reference to homosexuality, savvy viewers could certainly still pick up on the unspoken truth behind Brick’s gnawing shame; and puritanical eyebrows were raised in abundance over the sexual frankness of the dialogue (not to mention the sultry chemistry between the stars, surely two of the most beautiful people ever to step in front of a camera). These controversial elements no doubt contributed greatly to the film’s popularity at the time; but by today’s standards, of course, its content would barely warrant a PG rating. What then, if anything, is there to recommend this venerable artifact of mid-century sophistication to modern audiences? To begin with, the sets, the costumes, the cinematography- the entire production- is everything you would expect of a high-budget, top-notch MGM product; but the same is true of many infinitely less watchable films from the same era. What really matters here is the material. Even watered-down Williams is a treat to see and hear, particularly in the hands of a cast capable of bringing out the rich, musical literacy and the deep, resonant emotional landscape of his text; and though director Richard Brooks (who also co-wrote the sanitized screenplay with James Poe) crafted a relatively uninspired film version, cinematically speaking- particularly when contrasted with other Williams adaptations of the time, such as the earlier classic, A Streetcar Named Desire– he clearly had a strong enough understanding of the piece to evoke uniformly superb performances from his players. Recreating his role from the Broadway production, Burl Ives dominates his every scene- and appropriately so- as Big Daddy, overbearing all before him with a grim, determined Southern smile even when most assaulted by pain, whether emotional or physical. Matched against him is the great Judith Anderson, oddly cast but highly effective as Big Mama, creating a sympathetic portrait of a woman, hardened but unbeaten by a lifetime under her husband’s imposing shadow, desperately clinging to the illusions she has worked to maintain for herself and her family. Jack Carson is likable as older brother Gooper despite the ineffectual disinterest of a character forever dominated by the others around him; and, as his wife Mae, Madeleine Sherwood (another veteran of the Broadway production) balances him by being equally dis-likable, an embodiment of mean-spirited pettiness, hypocrisy and self-righteous entitlement that serves as the closest thing in the piece to a villain. Of course, all this stellar supporting work would be meaningless without equally strong performances from the leads, and the two iconic stars here give performances that rank among the finest of their careers. As Brick, Newman proved once and for all that his ability as an actor was as formidable as his steely-blue-eyed good looks; he gives a remarkable and definitive interpretation of the character, playing against those leading-man-looks to bring out the ugliness of Brick’s dissolute bitterness- the high-handed and deliberate cruelty, the obstinate refusal to face his demons, the willfully self-destructive embrace of his alcoholism- without ever completely obscuring his underlying sensitivity and compassion, creating a complete portrait of a good man crippled (both literally and metaphorically) by the effects of failure, regret, and shame. The keystone performance, however, comes from Taylor, at the peak of her astonishing beauty and the beginning of her reign as one of Hollywood’s most glamorous and beloved stars. It would be easy to play Maggie “the Cat” as an ambitious, tawdry social climber bent only on claiming the family fortune of a man she has married for money, but Taylor makes her so much more: she not only radiates the aching sexuality of a woman too long neglected, but also the determination and candor which make it clear that she alone has the strength to be Big Daddy’s true successor as the dominant force in this family, coupled with the earnest feeling that makes it possible for us to believe, in the end, that she has the power to “make the lie true.” That, ultimately, is what Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is about: in a world full of “mendacity,” it takes passion and, yes, love to make the difference between truth and illusion. This first and still most authentic film version, with all its Technicolor gloss and its soundstage artificiality, is Hollywood illusion at its most persuasive- but thanks to Miss Taylor and the rest of its remarkable cast, it has the real ring of truth about it, and that is what makes it a classic.