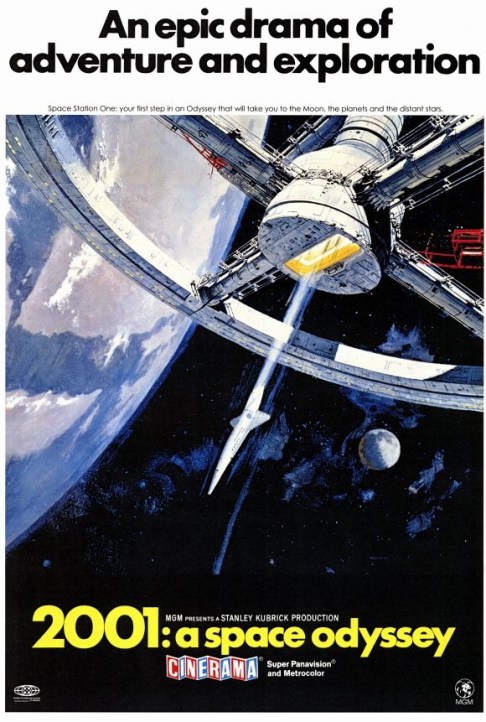

Today’s cinema adventure: Prometheus, the 2012 sci-fi thriller that marks the return of director Ridley Scott both to the genre and to the film franchise that made his name. A prequel of sorts to his 1979 classic, Alien, it follows the fate of a late-twenty-first-century space expedition which journeys to a distant planet in search of answers to the secret of human origin, revealing (partially) the background of the terrifying race of creatures that inhabited the earlier film and its sequels- but also establishing its own internal mythology, with a plot and a purpose completely independent of its predecessor, and tackling deeper, far-reaching philosophical themes along the way. Indeed, director Scott makes it clear from the very first frames that he has greater ambitions than just making a straightforward science fiction adventure: the opening shot is a direct copy of the one used by Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey– in fact, the entire credits sequence is reminiscent of an important scene from 2001, and throughout Prometheus there are countless echoes- some huge, some tiny- from that venerable masterpiece. This is appropriate enough, given that Scott’s film shares many of the central themes from Kubrick’s landmark opus, such as man’s continuing quest for knowledge and his uneasy relationship with the technology he has created to aid him in that quest; indeed, the central plot (the discovery of artifacts from earth’s ancient past leads to a space mission and a confrontation with the mysteries of our creation) is essentially the same in both films. Scott, however, working from the screenplay by John Spaihts and Lost co-creator Damon Lindelof, offers his own interpretation of these ideas; his is a much darker vision of our species and its place in the universe, and one which reflects the change in our collective consciousness in the 45 years since Kubrick made his film. In place of Kubrick’s somewhat ironic vision of a future shaped by nuclear age optimism and practicality, we are given a universe more closely resembling the one seen in Scott’s earlier visits to this genre: a place in which human flaws such as ego, greed, hostility, mistrust and duplicity run rampant; and where these qualities not only threaten to undermine the greater purpose but are seen to be shared by the very creative forces that shaped us. Not that Scott gives us a universe without hope- far from it. In Prometheus, hope is arguably the central issue, and holding onto it in the face of bleak nihilism can be seen as the one saving grace of our species- coupled with undying curiosity and armed with the knowledge of what has come before, it can keep us going even when there seems no purpose for doing so. In a way, Prometheus offers us an even more inspiring conclusion than 2001, suggesting that the secret of man’s creation and continuing renewal lies within ourselves, alongside the very seeds of our own destruction- no matter what our origins may be, we are self-determining creatures and not just pawns observing a cosmic waltz in which we may be a mere side effect.

All this conjuring of the spirit of 2001 may be justified by the needs of Scott’s intellectual premise, but it also serves as a means to pay homage to his cinematic influences; the visual and thematic reflections of Kubrick’s film are just the most obvious of his tributes to the works of those who have shaped his own vision, from the overt use of Lawrence of Arabia as an inspiration for one of the central characters to the more subtle nods in the direction of such diverse movies as Citizen Kane and Forbidden Planet. With such a pedigree, it would be nice to say that Prometheus is a worthy successor to the masterworks tagged within it; but despite its lofty goals, it is a film which suffers from the all-too-common malady of formula. The cinematic building blocks so reverently placed by Scott seem to promise a work of intelligence and depth- which, for the most part, he has given us- but as the plot unfolds towards its predictably cataclysmic conclusion, his movie falls into the familiar repetition of patterns we have seen ad infinitum: the characters’ fates can be foreseen from their virtues or flaws in the same way we can tell that the bad girls are going to get offed in a slasher film, pivotal plot elements are introduced with so many red flags we can instantly see where they will lead, and, of course, anyone familiar with the original Alien and its sequels will know from the outset where the story is headed, reducing the entire experience to a detached exercise in answering questions left over from the previous franchise entries. In addition, the level of tension, so expertly built and maintained by Scott in his original film, is here allowed to rise and fall so often and with so little payoff, that by the end we are not so much excited as we are mildly curious to see how things will finally play out. Furthermore, the insistence on maintaining a rigid connection to the concrete realism dictated by its cookie-cutter storyline prohibits the director from diverging from his linear plot into the absract flights of fancy that made 2001 such a groundbreaking work and prevents him from taking his cosmic themes into an esoteric realm where they can be more fully explored.

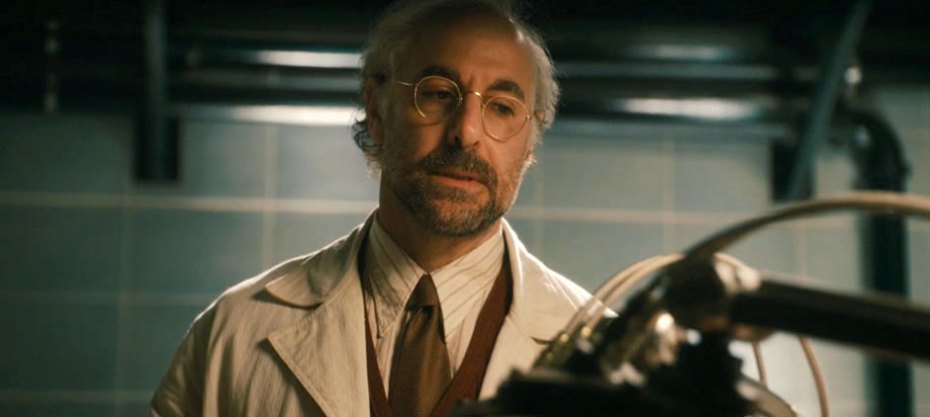

Don’t get me wrong: by any standards, Prometheus is a well-above-average film, an ambitious labor of love by a director of considerable talent; considering that its development and production history reads like an indictment of all that is wrong with the Hollywood process today, the fact that it offers so much substance along with its profit-minded formulaic plot is a miracle in itself. Scott has always been a director with remarkable gifts, particularly in visual terms, and this film certainly lives up to his reputation; it combines the immediacy of Alien with the elegiac reflection of Blade Runner; and, like both those examples, creates a stunning, immersive world for us to experience. Superbly photographed in 3-D by Dariusz Wolski, Prometheus presents a brilliant blend of its own shrewdly futuristic design and the H.R. Giger-inspired bio-technical look of the original Alien; and, to draw another comparison with 2001, it sets a new standard for special effects, with a look and a feel derived from dedication to the artistic purpose of the whole, not merely from a desire to dazzle us. This accomplishment is achieved, under the supervision of production designer Arthur Max, by a seamless blend of CG, traditional camera trickery, and live action footage, and it yields countless examples of big screen imagery which are surely destined to become iconic. All this technical wizardry is not wasted, notwithstanding the quibbles which mar the film’s narrative: Scott rises to the occasion throughout, creating moments of breathtaking beauty and visceral terror- in fact, the film’s most effective scenes (particularly a medically-themed sequence near the climax) are those which resurrect the creepy, primal body-horror around which the original was based and the fear of which is never far from our minds from the moment the exploration team lands. Aiding him in his struggle to rise above his mundane material is a fine cast which includes superb work from Charlize Theron (proving once again that she is Hollywood’s reigning ice queen), Idris Elba and Guy Pearce; standing out above the rest is the hypnotic Michael Fassbender, who provides further evidence of his substantial talent as the film’s most memorable and enigmatic character; and in the central role, Noomi Rapace makes a convincing transition from idealistic scientist to determined survivor, stirring favorable comparative memories of the franchise’s original heroine, Sigourney Weaver. The one sour performance comes from Logan Marshall-Green, whose hot-shot demeanor and club-rat looks make him not only unconvincing as a world-class scientist but also unlikable as a hero and poorly matched with Rapace’s much more sympathetic personality.

Prometheus has been anticipated as one of the year’s biggest film events, with much hype and secrecy surrounding its content and high expectations for both critical and commercial success. With all that pressure, it is not surprising that it has met, so far, with mixed reaction: hardcore fans of the genre have expressed disappointment with its emphasis on esoteric elements instead of on providing concrete answers to the mysteries it presents- many of which are left unrevealed, begging the development of a sequel despite the insistence of its makers that it is meant to be a stand-alone project- and serious-minded filmgoers have complained (as I did) of the reliance on cliché and formula in a plot which keeps it from fully realizing its higher goals. In the long term, who can really say where it will stand in the estimation of future cinemaphiles? What is certain now is that audiences seem to love it or hate it, which for me has always been the surest sign of artistic success. Summing up my own opinion, I would have to say that I loved it- with reservations. I can’t guarantee that you will share that view, but I can tell you that it’s worth a trip to your local theater to find out for yourself. You may not be satisfied, but you will almost certainly be stimulated and provoked, and isn’t that what art- and cinema in particular- is all about?

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1446714/

;