Today’s cinema adventure: The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s massively successful 2008 sequel to his earlier Batman Begins, tracking the continuing progress of DC Comics’ iconic hero in his quest to free Gotham City from the grip of rampant crime and corruption and pitting him against a new breed of criminal- the costumed madman known only as the Joker. Continuing his re-imagination of the comic-book premise as a crime drama grounded in realism, the director takes it even further this time around, creating a gritty, violent vision of urban warfare in which the line between right and wrong becomes blurred in a larger struggle between order and chaos. The formula obviously struck a nerve; the film broke box office records and earned the kind of massive critical accolades usually reserved for more “serious” fare.

Working from a story developed by Batman Begins co-writer David S. Goyer, Nolan this time fashions a screenplay with his brother, Jonathan, in which billionaire Bruce Wayne, working in unofficial partnership with Police Lt. Gordon, has made headway in the campaign to weaken the control of organized crime over Gotham City. With the rise of the city’s idealistic new D.A., Harvey Dent, he sees a chance to hand over his role as the city’s protector and at last embrace the comforts of a normal life; but a new threat arises in the form of the Joker, a disfigured psychopath in clownish makeup, who begins an escalating campaign of terror. To combat this new adversary, Wayne and Gordon join forces with Dent, and the trio works in secret alliance to put a stop to his deadly game before Gotham deteriorates into a state of total anarchy. The Nolans use their plot as a means to explore a wide variety of inter-connected themes, making the scope of The Dark Knight much wider and its moral landscape more ambiguous than its predecessor’s, and as a result they transform what is essentially a fantasy adventure into a complex parable about the ethical dilemmas of preserving order in the modern world. Throughout the film, the intricately plotted storyline is threaded with dialogue and situations that clearly evoke the complicated morality of post-9/11 society; the age-old cops-and-robbers scenario has been co-opted by a battle between ideologies, in which those who would protect society come dangerously close to becoming an even greater threat to it themselves. Indeed, the antagonist’s master plan is to subvert the established order by turning it against itself, exploiting the contradictions in its own rules and ethics to create an environment of fear and chaos in which he can, in the words of one character, “watch the world burn.” In the course of the action, we are given a remarkably detailed portrait of Gotham City- which serves as a microcosm of American civilization- which includes a look at its politicians, its media figures, its businessmen, its criminals, its public servants, and its average citizens; the effect of the city’s peril on its population is presented as a mirror to our own society, and the drama enacted by the key figures of the story reflects our efforts to reconcile the moral conflicts inherent in dealing with our own terrorized world. As the story moves relentlessly towards its climax, it raises questions about the implications of working outside the law for a greater good, the manipulation of public perception for political purposes, the ambiguous role of invasive technology in preserving communal security, the potential corruptibility of human nature, and the danger of becoming your enemy when you fight against him on his own terms. Most significantly, it examines the role of choice in the struggle to define humanity; whether our actions are dictated by chance and motivated by self-interest, or whether we are ultimately responsible for the decisions we make, for good or for ill.

If it sounds like heavy, existential themes dominate The Dark Knight, that’s because they do; but that doesn’t mean it’s a film that favors philosophical debate over a good story. Rather, the story is the debate. Nolan uses his epic themes to propel the action, leading us through the conditional parameters until the core issue is revealed at the heart of his plot. Batman and his allies, the self-sacrificing champions of order and justice, are pitted against the Joker, a self-serving personification of chaos and amorality. At every step of the game, the Joker challenges his opponents’ dedication and their beliefs, forcing them into no-win situations in which they have no choice but to act against their own principles; convinced of their hypocrisy and their fallibility, and confident that he can- and will- break their spirit, he manipulates the scenario not only to prove his point, but to inflict torment for his own gratification. It is this, perhaps, that Nolan suggests as the ultimate definition of evil- the pure selfishness that satisfies its own desires at the expense of others- and it is this basic quality that the Joker wishes to expose as the true nature of mankind. Whether or not he is right is certainly not resolved by the end of the movie- after all, there is still another chapter to come- but Nolan’s skill at cinematic storytelling ensures that the arguments on both sides are illustrated with a sense of urgency and an emphasis on action.

In fact, the action is virtually non-stop. Even when The Dark Knight concerns itself with quiet, more intimate matters, Nolan’s directorial choices give it a driving, restless feel- continuing the sense of momentum that he initiated in Batman Begins. His camera is almost never still, with slow zooms and pans in almost every shot, and he pieces things together with quick edits, giving us just enough of an image to establish what we’re seeing and then sharply moving on. He crams so much into the film this way that there are whole subplots which can go unnoticed without repeat viewings, and it allows him to provide an expansive view of the life of Gotham City into his 2 1/2 hour running time. He confidently moves his tale through its escalating developments with a speed that keeps the viewer on edge, establishing key points without belaboring them, relying on the completeness of his screenplay- and the intelligence of his audience- to ensure clarity. Likewise, he depends on the writing and the skill of his gifted actors to convey the important nuances of his characters that make the film so compelling, though he certainly takes the time to explore the dynamics of their relationships onscreen, rightly understanding the importance of this aspect in the overall scope of his vision.

Of course, however, as in any movie about a titanic struggle of heroes and villains, the primary focus is on thrilling action, and Nolan certainly delivers this in spades. Continuing in the vein of Batman Begins, he chooses to construct his movie with a minimum of computer trickery, instead utilizing live action stunt work filmed in actual locations or on elaborate soundstage sets. He fills his film with gripping set pieces, from the opening bank heist sequence- which rivals anything in the best of Hollywood’s caper films- to the climactic confused free-for-all in which Batman must fight a SWAT team to protect the Joker’s hapless hostages who have been disguised as his henchmen; in between are a breathtaking depiction of a nighttime kidnapping from Hong Kong’s tallest building and the movie’s action centerpiece- an extended urban roadway chase in which Batman rides his souped-up cycle to defend a police convoy from a semi-truck containing the heavily-armed Joker and his men. Adding to the excitement is the fact that Nolan chose to shoot these sequences- as well as some of the smaller-scale scenes- in an IMAX format, although the effect of this is somewhat diminished by viewing on a small screen.

In service of his visual spectacle, Nolan’s production team provides an impressive display of their talents; most significantly, perhaps, cinematographer Wally Pfister, who gives the film a style that is simultaneously slick and grimy, and appropriately creates a significantly darker look than that of the earlier film. The production designers, headed once more by Nathan Crowley, have revamped the technological aspects of Batman’s world- a redesigned, lightweight suit that makes the hero more agile, as well as the dazzlingly well-realized, aforementioned “batpod” that he rides into battle with his demented adversary, stand out as distinct advancements over the gadgetry in the previous chapter- and Gotham’s cityscape has been completely overhauled. Gone is the deco-flavored mix of nostalgic and futuristic elements that marked the city of Batman Begins; here we find an utterly contemporary metropolis of steel, plastic and glass, a world-class capitol of industry and commerce with shining citadels and utilitarian infrastructure that is more directly representative of the typical modern urban environment of America. Its familiarity adds another layer to the realism that is Nolan’s goal, and with this backdrop against which to play out his epic drama, the more implausible elements of the comic-book scenario are somehow more believable. The score, once again the product of collaboration between Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard, echoes the mood-oriented style of Batman Begins, but with even more of an emphasis on driving the pace with an undercurrent of rippling and restless rhythms, suggesting the chaos that threatens to envelop Gotham City.

Nolan’s modern re-invention of the Batman mythology, however, is most clearly and successfully exemplified by the one element of The Dark Knight that has- justifiably- received the most attention: the performance of Heath Ledger as the Joker. The young actor delivers a stunning portrait of this well-known character, accomplishing the seemingly impossible feat of giving us something completely unexpected and unlike any interpretation we have seen before. His psychotic clown is a million miles away from the fruity camp of Cesar Romero’s goofy TV persona, and totally unlike Jack Nicholson’s self-parodying turn in Tim Burton’s Batman film of two decades before. Ledger makes the character a frightening, dangerous madman, clearly deranged but chillingly sharp and lucid; we are given no background for him, aside from the conflicting stories he tells himself within the film, but we can plainly see that whatever traumatic occurrence has led to the development of his deeply disturbed personality, it has left him utterly and completely devoid of humanity. His makes it plain that his Joker lives for the thrill of the moment, taking great pleasure in pain- including his own, greeting each blow from his caped opponent with a rush of giddy adrenaline-laced delight. His voice, his physicality, the coldness of his eyes, all combine to create an unforgettable portrait of menace, and for the first time in the history of comic-based films, he has given us an utterly believable super-villain. The one completely human moment he exhibits comes late in the film, a reaction of genuine surprise over an unforeseen development which throws a wrench in the works of his master plan- it’s a subtle but dazzling moment which instantly casts into stark relief the sheer brilliance of everything we have seen from him before that. Ledger’s tragic death before the film’s release may have contributed to the publicity surrounding his work here, but had he lived the performance would still have stood as a triumph, and was fully deserving of the multitude of awards and accolades it received posthumously for him.

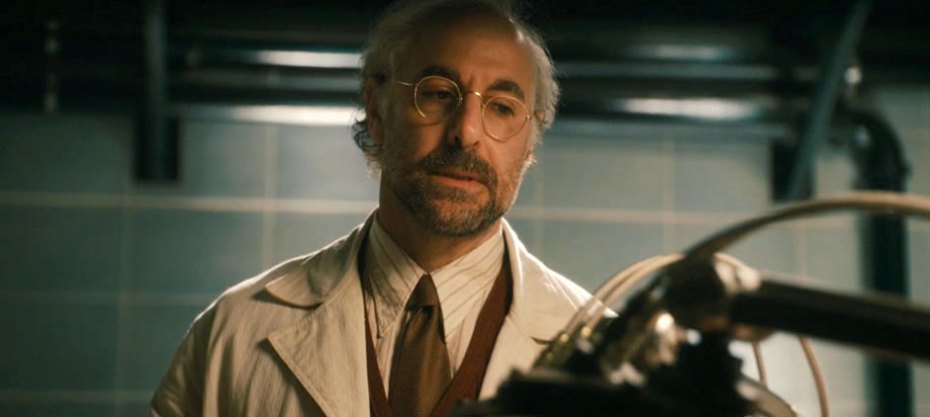

This is not to take credit away from any of his co-stars. Every member of Nolan’s cast gives a stellar effort, starting with Christian Bale, whose Batman is leaner and more haggard than in his previous appearance in the role, reflecting the maturity and the effects of the stress that have shaped him in the intervening years since Batman Begins. He gives the character a wearier edge, exuding more confidence but also more contempt for his criminal prey; even his Bruce Wayne seems a little worn down from all the partying with supermodels and prima ballerinas his public image requires him to do. Underneath it all, though, he clearly shows us the power of his dedication to the job he has appointed himself, and his refusal to yield to the Joker’s efforts to bring him down to a baser level is utterly convincing- particularly in light of the self-doubt he shows us in response to his costly failures- giving us the glimmer of hope we can cling to through the film’s dark finale. Returning as his trusted servant and co-conspirator, Alfred, is the magnificent Michael Caine, who continues to provide a grounding center of wisdom and genuine class, and whose chemistry with Bale offers the film’s strongest example of deep, close human connection. Maggie Gyllenhall replaces the absent Katie Holmes as Rachel, Bruce’s childhood friend and would-be sweetheart for whom he still carries a torch, and though it is somewhat jarring to see a different actress in the role, she provides a fine performance, making the character a strong, independent, and empowered woman, an equal partner in the battle against crime, rather than just another helpless female in need of rescue. Gary Oldman and Morgan Freeman continue to expand on their own brands of quiet heroism as Lt. Gordon and Lucius Fox, respectively; and, though his work was eclipsed by Ledger’s dazzling performance, Aaron Eckhart is equally superb, in his way, as Dent- who is both the film’s secondary hero and secondary villain, transforming from the dedicated “White Knight” whose unflinching integrity gives the city hope to the vengeful and deformed “Two-Face,” driven to madness by personal loss- and providing the perfect symbol for corrupt politics with his half-handsome, half-grotesque features.

The Dark Knight has been subject to much discussion and debate regarding its political messages; some have viewed it as an endorsement of hawkish, right-wing tactics in the war against terrorism, while some have declared it as an indictment of the dangers inherent in using such methods. Like most art- certainly most good art- it is ultimately a blank slate, a mirror in which the viewer sees their own perspectives reflected back; it seems to me that Nolan presents his subject matter without political agenda, exploring the thematic issues that arise out of the situation, but making no judgments, preferring to allow the viewer to draw their own conclusions. What interests Nolan much more, perhaps, is the issue of basic human nature; and though his vision has the dark and cynical trappings of the noir style that has been a clear influence on his work, and though many have seen the film as a story of evil overwhelming good, at its heart is the message that, though some may waver or even fall, there is a desire inside us to do the right thing; as long as there are men who hold onto the standard of decency and set an example- even an illusory one- there is hope for us yet to conquer the forces of darkness that threaten our world, both from within and without. That is an idea the filmmaker will explore further in the third (and supposedly final) installment of his Batman cycle; but, at least as this one rolls to an end, we can still believe in a champion that represents the best in us all, and as far as I’m concerned, that’s a pretty optimistic note for such a “dark” movie to end on.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0468569/