When “Brokeback Mountain” arrived on the scene in 2005, it was almost unthinkable that a big-budget Hollywood film about a same-sex romance between two sheep herders could even get made, let alone go on to become a critically-lauded, multi-award-winning cultural phenomenon. To be sure, it had its share of detractors, but the favor it gained within the mainstream was a clear sign that the tide was turning with regards to LGBTQ acceptance.

In those pre-marriage-equality days, its tragic tale of love thwarted by social intolerance was a somber testament of truth for the millions of queer people who had lived such lives through the generations that had come before – and make no mistake, it’s still a story that needs to be told. Even so, there are many who felt that the film’s star-crossed lovers deserved a happier fate.

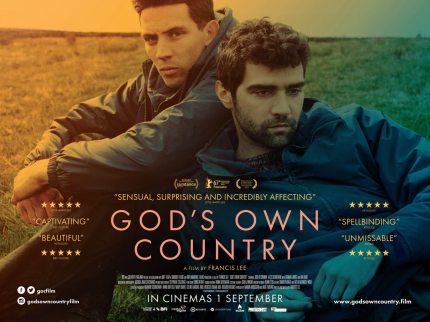

Now, twelve years later, they just might get a second chance – at least by proxy – in filmmaker Francis Lee’s quietly breathtaking debut feature, “God’s Own Country.”

Set in the bleak highlands of modern-day Yorkshire, it centers on Johnny Saxby, a young man who lives and works on his family’s struggling farm. By night, he escapes from his grueling existence by drinking himself into a stupor at the village pub; occasionally, he finds temporary escape in anonymous sexual encounters with other men at the cattle auction or, presumably, from the surrounding area. His routine is disrupted, however, when his father brings in Gheorghe, a Romanian immigrant worker, to help with the sheep during lambing season; though he is at first resentful and abusive of the new hired hand, a powerful attraction soon develops between the two men.

How things unfold from there is the main business of the movie, and it would be bad form to reveal how it eventually plays out; suffice to say that, despite the similarities in their subject matter, “God’s Own Country” is a very different experience from “Brokeback.”

It is, of course, patently unfair to define Lee’s heartfelt and highly personal film in relation to another movie, no matter how much the comparison begs to be made – but it’s hard to avoid pointing out at least one particularly telling detail. In “Brokeback,” the two protagonists face homophobia from both without and within; but in the contemporary world of “God’s Own Country,” that homophobia is more of a phantom threat than a concrete one. The people around Johnny seem to accept his sexuality; and although he himself struggles with internalized shame, it may have less to do with being gay than it does with a fear of intimacy.

It’s this that makes the movie as far removed from “Brokeback” in tone and attitude as it is in the time and place of its setting, and it makes all the difference.

Lee’s film is a patient, understated, and touching portrait of two men as they find the courage to break through barriers – not social, but personal – to reach each other. It’s a struggle we’ve seen explored by heterosexual lovers in countless romantic dramas, but for gay couples on the screen the obstacles have historically been cultural or political. Though such factors may lie at the root of Johnny and Gheorghe’s issues, there is no need for them to change the world to be together – only themselves. In this way, their story is perhaps more closely related to Andrew Haigh’s excellent “Weekend” than it is to that other sheep wrangler movie.

Comparisons aside, “God’s Own Country” stands tall on its own considerable merits. Inspired by his coming of age in Yorkshire (the movie was filmed in his own village, with the farm where he grew up only a short distance from the shooting location), Lee has written and crafted a lovingly detailed work, as rigorous in its painstaking authenticity as it is poetic in its cinematic expression.

There’s much to appreciate in Lee’s directorial approach. He proves himself a master of visual storytelling, communicating some of the film’s most potent moments with little or no dialogue, and orchestrating a rich symbolic subtext with subtle visual cues throughout – like the muted reds and blues of Gheorghe’s knit sweater, which make it shine amidst the movie’s stark grey palette like a multi-hued beacon of hope. He is equally shrewd in what he doesn’t show; he largely eschews the wide landscapes typical of such pastoral romances, instead keeping his camera – and the story – focused on the personal and intimate.

He also draws superb performances from his actors. Josh O’Connor and Alec Secareanu make Johnny and Gheorghe, respectively, as genuine as they are endearing; their natural ease with their surroundings– Lee put them to work on a farm for several weeks before shooting – underscores and enhances not only the realism of their acting but of the movie itself. Most importantly, they have a rare chemistry that wins the audience from their first meeting – and places their love scenes among the sexiest big-screen pairings in recent memory.

In the smaller (but crucial) roles of Johnny’s father and grandmother, Ian Hart and Gemma Jones give quiet, dignified eloquence to characters who, in a lesser film, might have been rendered as course and one-dimensional stereotypes. Far from being antagonists, they provide a rich and fertile ground from which the film’s love story can grow.

It should be noted that “God’s Own Country” does contain some full-frontal nudity and relatively explicit sexual content. This will doubtless be reason enough to entice many viewers within the film’s target audience, but there is so much more in this little gem of a British import to warrant seeking it out.

Though it may not attract much mainstream attention, “God’s Own Country” feels important. When a movie about two men who fall in love with each other doesn’t feel the need to justify its own existence by advancing a social or political agenda, it’s proof that the turn of the tide signaled by “Brokeback,” not so very long ago, has carried us at last to an era in which a “gay movie” can simply be called “a movie.”

The fact that it’s also an excellent movie is a welcome bonus.

“The Haunting” (1963) – Even if seems tame by today’s standards, director Robert Wise’s adaptation of a short novel by Shirley Jackson is still renowned for the way it uses mood, atmosphere, and suggestion to generate chills. More to the point for LGBTQ audiences is the presence of Claire Bloom as an openly lesbian character (Claire Bloom), whose sympathetic portrayal is devoid of the dark, predatory overtones that go hand-in-hand with such characters in other pre-Stonewall films. For those with a taste for brainy, psychological horror movies, this one is essential viewing.

“The Haunting” (1963) – Even if seems tame by today’s standards, director Robert Wise’s adaptation of a short novel by Shirley Jackson is still renowned for the way it uses mood, atmosphere, and suggestion to generate chills. More to the point for LGBTQ audiences is the presence of Claire Bloom as an openly lesbian character (Claire Bloom), whose sympathetic portrayal is devoid of the dark, predatory overtones that go hand-in-hand with such characters in other pre-Stonewall films. For those with a taste for brainy, psychological horror movies, this one is essential viewing. “Blood for Dracula” AKA “Andy Warhol’s Dracula” (1974) – Although there is nothing explicitly queer about the plot of this cheaply-produced French-Italian opus, the influence of director Paul Morrissey and the presence of quintessential “trade” pin-up boy Joe Dallesandro – not to mention Warhol as producer, though as usual he had little involvement in the actual making of the movie – make it intrinsically gay. The ridiculous plot, in which the famous Count (Udo Kier) is dying due to a shortage of virgins from whom to suck the blood he needs to survive, is a flimsy excuse for loads of gore and nudity. Sure, it’s trash – but with Warhol’s name above the title, you can convince yourself that it’s art.

“Blood for Dracula” AKA “Andy Warhol’s Dracula” (1974) – Although there is nothing explicitly queer about the plot of this cheaply-produced French-Italian opus, the influence of director Paul Morrissey and the presence of quintessential “trade” pin-up boy Joe Dallesandro – not to mention Warhol as producer, though as usual he had little involvement in the actual making of the movie – make it intrinsically gay. The ridiculous plot, in which the famous Count (Udo Kier) is dying due to a shortage of virgins from whom to suck the blood he needs to survive, is a flimsy excuse for loads of gore and nudity. Sure, it’s trash – but with Warhol’s name above the title, you can convince yourself that it’s art. “Phantom of the Paradise” (1974) – Again, the plot isn’t gay, and in this case neither was the director (Brian DePalma). Even so, the level of over-the-top glitz and orgiastic glam makes this bizarre horror-rock-musical a camp-fest of the highest order. Starring unlikely 70s sensation Paul Williams as a Satanic music producer who ensnares a disfigured composer and a beautiful singer (Jessica Harper) into creating a rock-and-roll opera based on the story of Faust, it also features Gerrit Graham as a flamboyant glam-rocker named Beef and a whole bevy of beautiful young bodies as it re-imagines “The Phantom of the Opera” with a few touches of “Dorian Gray” thrown in for good measure. Sure, the pre-disco song score (also by Williams) may not have as much modern gay-appeal as some viewers might like, but it’s worth getting over that for the overwrought silliness of the whole thing.

“Phantom of the Paradise” (1974) – Again, the plot isn’t gay, and in this case neither was the director (Brian DePalma). Even so, the level of over-the-top glitz and orgiastic glam makes this bizarre horror-rock-musical a camp-fest of the highest order. Starring unlikely 70s sensation Paul Williams as a Satanic music producer who ensnares a disfigured composer and a beautiful singer (Jessica Harper) into creating a rock-and-roll opera based on the story of Faust, it also features Gerrit Graham as a flamboyant glam-rocker named Beef and a whole bevy of beautiful young bodies as it re-imagines “The Phantom of the Opera” with a few touches of “Dorian Gray” thrown in for good measure. Sure, the pre-disco song score (also by Williams) may not have as much modern gay-appeal as some viewers might like, but it’s worth getting over that for the overwrought silliness of the whole thing. “The Fourth Man (De vierde man)” (1983) – This one isn’t exactly horror, but it’s unsettling vibe is far more likely to make you squirm than most of the so-called fright flicks that try to scare you with ghouls and gore. Crafted by Dutch director Paul Verhoeven (years before he gave us a different kind of horror with “Showgirls”), it’s the sexy tale of an alcoholic writer who becomes involved with an icy blonde, despite visions of the Virgin Mary warning him that she might be a killer. Things get more complicated when he finds himself attracted to her other boyfriend – and the visions get a lot hotter. More suspenseful than scary, but you’ll still be wary of scissors for awhile afterwards.

“The Fourth Man (De vierde man)” (1983) – This one isn’t exactly horror, but it’s unsettling vibe is far more likely to make you squirm than most of the so-called fright flicks that try to scare you with ghouls and gore. Crafted by Dutch director Paul Verhoeven (years before he gave us a different kind of horror with “Showgirls”), it’s the sexy tale of an alcoholic writer who becomes involved with an icy blonde, despite visions of the Virgin Mary warning him that she might be a killer. Things get more complicated when he finds himself attracted to her other boyfriend – and the visions get a lot hotter. More suspenseful than scary, but you’ll still be wary of scissors for awhile afterwards. “Stranger by the Lake (L’Inconnu du lac)” (2013) – This brooding French thriller plays out under bright sunlight, but it’s still probably the scariest movie on the list. A young man spends his summer at a lakeside beach where gay men come to cruise, witnesses a murder, and finds himself drawn into a romance with the killer. It’s all very Hitchcockian, and director Alain Guiraudie manipulates our sympathies just like the Master himself. Yes, it features full-frontal nudity and some fairly explicit sex scenes – but it also delivers a slow-building thrill ride which leaves you with a lingering sense of unease.

“Stranger by the Lake (L’Inconnu du lac)” (2013) – This brooding French thriller plays out under bright sunlight, but it’s still probably the scariest movie on the list. A young man spends his summer at a lakeside beach where gay men come to cruise, witnesses a murder, and finds himself drawn into a romance with the killer. It’s all very Hitchcockian, and director Alain Guiraudie manipulates our sympathies just like the Master himself. Yes, it features full-frontal nudity and some fairly explicit sex scenes – but it also delivers a slow-building thrill ride which leaves you with a lingering sense of unease. When Ridley Scott’s dystopian neo-noir sci-fi opus opened in 1982, it was overshadowed at the box office – along with a number of other worthy films – by the juggernaut that was Steven Spielberg’s “E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial.” Consequently, it was deemed by the then-reigning Hollywood pundits to be a misfire, and critics seemed to echo that sentiment; though praised for its imaginative visual design – now regarded as influential and iconic – and its provocative thematic explorations, it was greeted with middling reviews that, taken together, marked it as an “interesting failure.”

When Ridley Scott’s dystopian neo-noir sci-fi opus opened in 1982, it was overshadowed at the box office – along with a number of other worthy films – by the juggernaut that was Steven Spielberg’s “E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial.” Consequently, it was deemed by the then-reigning Hollywood pundits to be a misfire, and critics seemed to echo that sentiment; though praised for its imaginative visual design – now regarded as influential and iconic – and its provocative thematic explorations, it was greeted with middling reviews that, taken together, marked it as an “interesting failure.”

Today’s Cinema Adventure was originally published in

Today’s Cinema Adventure was originally published in