Today’s cinema adventure: Moonrise Kingdom, a 2012 feature that lets you know, from its very first frame, that it is the work of filmmaker Wes Anderson. The quirky, bittersweet tale of a pair of star-crossed 12-year-old misfits who enact a plan to run away together, it is a film that draws heavily on the entire repertoire of its indie-icon director; all the familiar elements are here, from the visual style of vivid colors and symmetrically-framed shots to the thematic elements of dysfunctional family structures and ritualized personal mythologies. Drawn in from the start by the methodical introduction of its characters (another Anderson trademark, here cleverly assisted by the use of Benjamin Britten’s “A Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra” on the soundtrack), we are transported to a world at once fantastical and mundane, a nostalgic landscape of mid-century middle class life transplanted to a remote New England island setting; it is a place where the comfortable trappings of civilization exist in the midst of a verdant but unpredictable wilderness, a delicate balance reflected by its inhabitants’ constant struggle to contain the unfettered dreams of childhood by enforcing the rules of the adult world. Here, the local scouting organization seems to carry as much civic authority as the police force (which appears to be comprised of a single officer), a meteorological researcher takes on the role of mysterious, omniscient sage, and the larger social order is dictated by a tenuous connection with an outside world represented by various austere personages mostly present only at the other end of a telephone line. Within these oddball, darkly whimsical surroundings, Anderson unfolds a coming-of-age story, told from the perspective of the two children at its center, in which it becomes clear that the adult characters, for the most part, are the ones who must break through the barriers created by the frustration of their own youthful fantasies; the grown-ups are the ones who must “come-of-age,” and only then can the children- who think and behave in a highly adult fashion, or at least their attempted approximation of it- truly be allowed their childhood. This inversion of formula, in which the juvenile protagonists serve as catalysts for the transformation of their adult counterparts, is certainly nothing new: it has been explored in films ranging from early classics like Chaplin’s The Kid to contemporary blockbusters like Super 8; in particular, Anderson’s film seems to draw heavily on that mid-century classic of the genre, Disney’s The Parent Trap. This, however, is in no way meant to imply that Moonrise Kingdom is derivative or full of clichés- on the contrary, thanks to Anderson’s characteristically disarming wit and pseudo-subversive charm, it is as fresh and surprising a moviegoing experience as one could hope. It’s probably the best Wes Anderson movie since The Royal Tennenbaums; and, of course, though the gifted director may take the lion’s share of credit for its success, it is a combination of elements provided by a worthy group of collaborators.

To begin with, the screenplay, co-written with Anderson by Roman Coppola, is full of the kind of offbeat delights we have come to expect from this director: populated with characters simultaneously familiar and unique, comprised of inventive circumstances and conceits through which the story and its various sub-plots flow, and infused with a magical tone that nevertheless keeps ever-present the potential for serious real-life consequences; the proceedings never lose their underlying weight, but they are peppered with humor throughout, ranging from the dry to the morbid, and usually unexpected; and the abundant heavy-handed symbolism (place names like “Summer’s End,” a tree house impossibly positioned at the top of a very tall tree) is treated with such good-natured irony that it comes across as clever instead of just obvious. Anderson’s trademark visual style is captured with an almost-surreal crispness and color by cinematographer Robert D. Yeoman, and likewise contributing to the distinctive look of the film is remarkable work by Art Director Gerald Sullivan, Set Decorator Kris Moran, and Costume Designer Kasia Walicka-Maimone, who together create an eclectic style that resembles a collision of the catalogues from L.L. Bean and Eames Design Studio. As for the soundtrack, Anderson relies both on charming original music by Alexandre Desplat and, as always, a mix of obscure-but-familiar recordings- this time mostly eschewing his usual pop/rock choices for classical selections by Britten (the aforementioned piece as well as others) and Saint-Saëns, juxtaposed with the mournful crooning of Hank Williams.

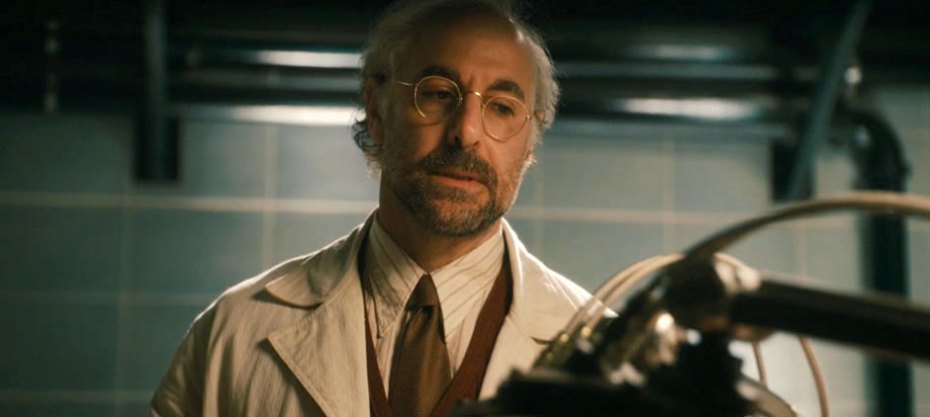

Of course, it is the ensemble cast that must ultimately bring Anderson’s cinematic symphony to life, and each member, without exception, is right on key. Edward Norton is tremendously likable as the plucky and earnest scoutmaster; Bruce Willis, as the local police captain, plays nicely against type while still taking advantage of his image as a tough man of action; Frances McDormand and Anderson perennial Bill Murray manage to capture the percolating bitterness of a long-embattled couple without making them unsympathetic; the ever-divine Tilda Swinton radiates a kind of institutional anti-Mary-Poppins vibe as a no-nonsense bureaucrat known simply as “Social Services;” Bob Balaban, Harvey Keitel and Jason Schwartzman (another Anderson stalwart) bring their own distinctive gifts to smaller roles; and an array of young actors contribute a spectrum of personalities as the scout troupe that gets caught up in the action. Despite this impressive collection of performances, however, the shining stars of Moonrise Kingdom are Kara Heyward and Jared Gilman, as the two pre-teen lovers around which the story revolves. Each underplay their characters with surprising skill and maturity, capturing the dispassionate detachment affected by these antisocial youngsters while still conveying the sweetness that lurks beneath it, and complementing each other’s work with a chemistry that is rarely seen in screen pairings between seasoned adult professionals; it’s their show, and it is a testament to their talent (and their director’s) that, despite being surrounded by a gallery of all-star heavyweights that includes two Oscar-winners and several other nominees, nobody even comes close to stealing it from them.

Moonrise Kingdom is one of those rare movie experiences that creeps up on you. After seeing it, I knew I liked it immediately, but it wasn’t until it had sunk in overnight that I realized just how much. There is a lot to take in: a plethora of details that Anderson meticulously arranges, just as his characters often arrange the contents of their suitcases or the objects on their desk; and just as those everyday items are transformed into talismans and icons by their owners, so too are all the pieces of Anderson’s movie invested with a significance that gives them a subliminal, cumulative effect when woven together into the whole. By the end of Moonrise Kingdom, you find that you’ve been moved on a level so deep, it doesn’t even have a name, and you didn’t even know it was happening. It’s a feeling that makes all the delights of the previous 90 minutes seem even more rewarding. Sadly, in a season full of mysterious alien beings and comic book action heroes, this little film is likely to be overlooked by a majority of moviegoers. Don’t be one of them: go and see Moonrise Kingdom as soon as possible; it will likely be only the first of many times.