Today’s Cinema Adventure was originally published in

Today’s Cinema Adventure was originally published in

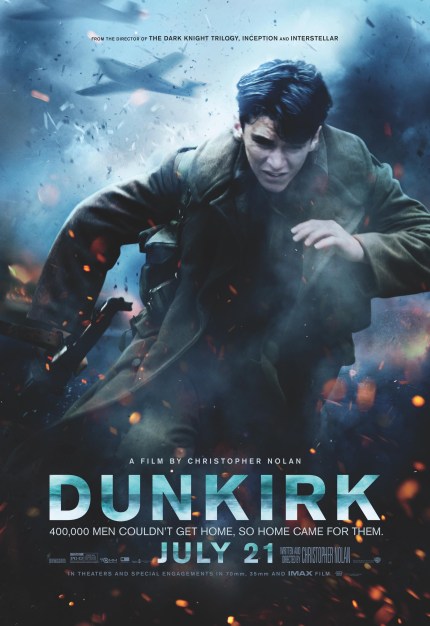

Christopher Nolan may be one of the most prominent of modern filmmakers, but he is surprisingly old-fashioned.

Consider his newest film, the highly-anticipated WWII drama, “Dunkirk.” In tackling a war movie (one of the oldest cinematic genres imaginable), he relies mostly on tricks of the trade established since the silent era, eschewing dialogue in favor of visual storytelling and favoring practical effects over computerized ones.

Not only that, he continues to champion the use of film over digital cinematography. “Dunkirk” is one of the rare contemporary films to be shot on widescreen film stock and presented in 70 MM format, delivering an experience that feels like one of those classic big screen extravaganzas of old.

Despite his tried-and-true approach, though, Nolan also brings his own contemporary perspective to the mix; this combination results in not only the most immersive, visually impressive war film in recent memory, but also the most thoughtful and challenging.

For those who need a brief history lesson, Dunkirk is a town on the French coast of the English Channel where hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers were trapped in the summer of 1940. Surrounded by Nazi forces, these combined English, French, and Belgian troops awaited evacuation on the beach while being pummeled from air and sea. Nolan’s film tells the story of their miraculous rescue from this dire situation.

Challenged with the task of capturing such an epic event in a way that brings it to his audience as concisely as possible, Nolan has chosen to split his movie into three interwoven stories. In one, we follow a young English soldier on the beach as he struggles to survive; in another, a civilian boat captain answers the call for private vessels to assist in the evacuation and sets sail across the Channel with his son and a young deck hand; and in the third, British fighter pilots attempt to fend off attacks against the rescue ships and stranded troops by engaging Nazi planes in dogfights above the beach.

Through these separate plotlines, Nolan raises the individual stakes within each story while building the tension that drives the larger narrative, providing a cumulative payoff when they finally come together for the climactic sequence they all share.

It’s this structure where Nolan most notably breaks from traditional style. Although the interwoven narrative is not, in itself, an unusual device, the director adds an extra layer by playing tricks with the passage of time. Without giving anything away, it’s safe to say that there are frequent moments when it’s difficult to tell where each storyline is in relation to the others – or to the over-arching action. The result is a disorientation which contributes to the overall sense of being in the midst of battle. It’s a challenging conceit, and although Nolan plainly sets up the rules early in the film, some viewers are bound to find it confusing.

Like any “auteur” filmmaker, Nolan’s entire of body of work explores recurring themes and repeated elements which make them distinctly and unmistakably his own. He has always been preoccupied with time in his movies, so it’s no surprise that he brings this obsession into “Dunkirk.”

The trouble with auteurs, however, is that appreciation of their work becomes a matter of taste which affects their entire canon. If one doesn’t like Nolan’s trademark blend of mind-bending narrative style and coldly philosophical thematic underpinnings, one is likely to find all of his movies unsatisfying. For that reason, “Dunkirk” will almost certainly frustrate those who are unimpressed with its director’s creative quirks.

That said, for those who are attuned to Nolan’s vision, “Dunkirk” is a truly magnificent film – possibly his best work to date – which embraces the form of the traditional war picture while simultaneously re-inventing it. It’s full of tropes, but the complexity with which Nolan infuses them makes them feel fresh, allowing him to use them as comfortable touchstones as he takes us on an intense journey through the harrowing and hellish landscape of war.

That journey would certainly not be possible without the sheer scope and size of his imagery (captured by cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema); but equally important is Hans Zimmer’s remarkable electronic score, which blends the thundering, sternum-shaking noises of combat so seamlessly into the ever-ascending music that it creates a kind of aural cocoon in which inner and outer realities merge. This, combined with the expert editing by Lee Smith, allows Nolan to deliver a movie which avoids overt manipulation and sentimentality yet offers sublime moments of accumulated empathy that may require a tissue or two from some viewers.

As for the cast, it’s a true ensemble, in which established stars (Tom Hardy, Mark Rylance, Kenneth Branagh, Cillian Murphy) serve side by side with lesser-known faces. The entire company deserves equal praise, but for reasons of space I will limit myself to singling out One Direction’s Harry Styles, in his first screen role as one of the soldiers awaiting rescue, who belies any notion of stunt-casting with an ego-free performance that stands on its own merit alongside those of his on-screen cohorts.

It must be mentioned that “Dunkirk” has received some criticism for its lack of diversity. While the majority of personnel involved in the real-life evacuation were undoubtedly white men, there were also men of color on that beach, none of whom appear onscreen. In addition, though the film does feature a few fleeting glimpses of women, they are more or less relegated to the background. It’s necessary to take note of such oversights as part of the important ongoing conversation about “whitewashing” in the film industry,

Still, in terms of judging the film for what it shows us (and not what it doesn’t), “Dunkirk” is powerful cinematic art. Though not overtly an “anti-war” film, it shows us the chaos of war alongside both the best and worst of what it brings out in humanity, without sentimentality or judgment. It focuses on survival over heroism, yet reveals that compassion leads to heroic acts. Perhaps most impressively, it avoids political commentary while inspiring us to find hope in the face of overwhelming oppression and defeat.

That alone makes “Dunkirk” a profoundly suitable war movie for these troubled times.

“The Haunting” (1963) – Even if seems tame by today’s standards, director Robert Wise’s adaptation of a short novel by Shirley Jackson is still renowned for the way it uses mood, atmosphere, and suggestion to generate chills. More to the point for LGBTQ audiences is the presence of Claire Bloom as an openly lesbian character (Claire Bloom), whose sympathetic portrayal is devoid of the dark, predatory overtones that go hand-in-hand with such characters in other pre-Stonewall films. For those with a taste for brainy, psychological horror movies, this one is essential viewing.

“The Haunting” (1963) – Even if seems tame by today’s standards, director Robert Wise’s adaptation of a short novel by Shirley Jackson is still renowned for the way it uses mood, atmosphere, and suggestion to generate chills. More to the point for LGBTQ audiences is the presence of Claire Bloom as an openly lesbian character (Claire Bloom), whose sympathetic portrayal is devoid of the dark, predatory overtones that go hand-in-hand with such characters in other pre-Stonewall films. For those with a taste for brainy, psychological horror movies, this one is essential viewing. “Blood for Dracula” AKA “Andy Warhol’s Dracula” (1974) – Although there is nothing explicitly queer about the plot of this cheaply-produced French-Italian opus, the influence of director Paul Morrissey and the presence of quintessential “trade” pin-up boy Joe Dallesandro – not to mention Warhol as producer, though as usual he had little involvement in the actual making of the movie – make it intrinsically gay. The ridiculous plot, in which the famous Count (Udo Kier) is dying due to a shortage of virgins from whom to suck the blood he needs to survive, is a flimsy excuse for loads of gore and nudity. Sure, it’s trash – but with Warhol’s name above the title, you can convince yourself that it’s art.

“Blood for Dracula” AKA “Andy Warhol’s Dracula” (1974) – Although there is nothing explicitly queer about the plot of this cheaply-produced French-Italian opus, the influence of director Paul Morrissey and the presence of quintessential “trade” pin-up boy Joe Dallesandro – not to mention Warhol as producer, though as usual he had little involvement in the actual making of the movie – make it intrinsically gay. The ridiculous plot, in which the famous Count (Udo Kier) is dying due to a shortage of virgins from whom to suck the blood he needs to survive, is a flimsy excuse for loads of gore and nudity. Sure, it’s trash – but with Warhol’s name above the title, you can convince yourself that it’s art. “Phantom of the Paradise” (1974) – Again, the plot isn’t gay, and in this case neither was the director (Brian DePalma). Even so, the level of over-the-top glitz and orgiastic glam makes this bizarre horror-rock-musical a camp-fest of the highest order. Starring unlikely 70s sensation Paul Williams as a Satanic music producer who ensnares a disfigured composer and a beautiful singer (Jessica Harper) into creating a rock-and-roll opera based on the story of Faust, it also features Gerrit Graham as a flamboyant glam-rocker named Beef and a whole bevy of beautiful young bodies as it re-imagines “The Phantom of the Opera” with a few touches of “Dorian Gray” thrown in for good measure. Sure, the pre-disco song score (also by Williams) may not have as much modern gay-appeal as some viewers might like, but it’s worth getting over that for the overwrought silliness of the whole thing.

“Phantom of the Paradise” (1974) – Again, the plot isn’t gay, and in this case neither was the director (Brian DePalma). Even so, the level of over-the-top glitz and orgiastic glam makes this bizarre horror-rock-musical a camp-fest of the highest order. Starring unlikely 70s sensation Paul Williams as a Satanic music producer who ensnares a disfigured composer and a beautiful singer (Jessica Harper) into creating a rock-and-roll opera based on the story of Faust, it also features Gerrit Graham as a flamboyant glam-rocker named Beef and a whole bevy of beautiful young bodies as it re-imagines “The Phantom of the Opera” with a few touches of “Dorian Gray” thrown in for good measure. Sure, the pre-disco song score (also by Williams) may not have as much modern gay-appeal as some viewers might like, but it’s worth getting over that for the overwrought silliness of the whole thing. “The Fourth Man (De vierde man)” (1983) – This one isn’t exactly horror, but it’s unsettling vibe is far more likely to make you squirm than most of the so-called fright flicks that try to scare you with ghouls and gore. Crafted by Dutch director Paul Verhoeven (years before he gave us a different kind of horror with “Showgirls”), it’s the sexy tale of an alcoholic writer who becomes involved with an icy blonde, despite visions of the Virgin Mary warning him that she might be a killer. Things get more complicated when he finds himself attracted to her other boyfriend – and the visions get a lot hotter. More suspenseful than scary, but you’ll still be wary of scissors for awhile afterwards.

“The Fourth Man (De vierde man)” (1983) – This one isn’t exactly horror, but it’s unsettling vibe is far more likely to make you squirm than most of the so-called fright flicks that try to scare you with ghouls and gore. Crafted by Dutch director Paul Verhoeven (years before he gave us a different kind of horror with “Showgirls”), it’s the sexy tale of an alcoholic writer who becomes involved with an icy blonde, despite visions of the Virgin Mary warning him that she might be a killer. Things get more complicated when he finds himself attracted to her other boyfriend – and the visions get a lot hotter. More suspenseful than scary, but you’ll still be wary of scissors for awhile afterwards. “Stranger by the Lake (L’Inconnu du lac)” (2013) – This brooding French thriller plays out under bright sunlight, but it’s still probably the scariest movie on the list. A young man spends his summer at a lakeside beach where gay men come to cruise, witnesses a murder, and finds himself drawn into a romance with the killer. It’s all very Hitchcockian, and director Alain Guiraudie manipulates our sympathies just like the Master himself. Yes, it features full-frontal nudity and some fairly explicit sex scenes – but it also delivers a slow-building thrill ride which leaves you with a lingering sense of unease.

“Stranger by the Lake (L’Inconnu du lac)” (2013) – This brooding French thriller plays out under bright sunlight, but it’s still probably the scariest movie on the list. A young man spends his summer at a lakeside beach where gay men come to cruise, witnesses a murder, and finds himself drawn into a romance with the killer. It’s all very Hitchcockian, and director Alain Guiraudie manipulates our sympathies just like the Master himself. Yes, it features full-frontal nudity and some fairly explicit sex scenes – but it also delivers a slow-building thrill ride which leaves you with a lingering sense of unease. Today’s Cinema Adventure was originally published in

Today’s Cinema Adventure was originally published in