Today’s cinema adventure: Eating Raoul, the dark 1982 low-budget satire which became a surprise hit and helped to start a wave of goofy “camp” comedies that pervaded the rest of the decade. Director/co-writer Paul Bartel, an exploitation cinema veteran, also stars with longtime friend and frequent co-star Mary Woronov as a married pair of sexual squares who lure “swingers” to their Hollywood apartment and kill them with a frying pan in order to finance their dream of opening a restaurant. Macabre as the premise seems- and in spite of a plot which features such elements as rape, serial murder and cannibalism- the film is kept light and fun by a healthy dose of good-natured kitsch and by its ridiculously over-the-top portrayal of the lurid “swinger” culture and its sexually liberated denizens. Bartel and Richard Blackburn’s screenplay is loaded with pseudo-shocking dialogue which exploits the ridiculousness of both prudish repression and extreme sexuality, peppered with great deadpan one-liners, and thematically unified by an exploration of the depravity hiding just under even the most respectable-seeming surfaces. Clever writing aside, the primary factor in the film’s success is the charm of its leading players: Bartel is somehow likeable and endearing despite his pompously indignant and über-nerdy persona; former Warhol “superstar” Woronov is a complex confection, undercutting her character’s uptight austerity with smoldering sensuality and a girlish vulnerability; and the chemistry between these oddball stars is palpable- they are clearly driven by the same skewed vision. Rounding out the main cast is Robert Beltran, equally charming and sympathetic as Raoul, the hot-blooded Latino hoodlum who attempts to blackmail and come between the couple- and whose ultimate fate is foreshadowed by the tongue-in-cheek title of the film. In addition, there are some delightful cameos by comedic masters such as Buck Henry, Ed Begley, Jr., and the incomparable Edie McClurg. The sordid proceedings play out against a now-nostalgic backdrop of seedy Los Angeles locations, accompanied by a quirky and eclectic soundtrack and driven at a brisk pace by Bartel’s quietly masterful direction. Don’t get me wrong here- Eating Raoul is by no means a masterpiece, even in the world of underground cinema- it lacks the anarchic, subversive edginess of a John Waters film, and its “shocks” are pretty tame, even by 1982 standards- but it is nevertheless a delight to watch, perhaps because for all its satirical snarkiness and its unsavory subject matter, there is an unmistakable sweetness at the center of its black little heart.

Category Archives: 1980s

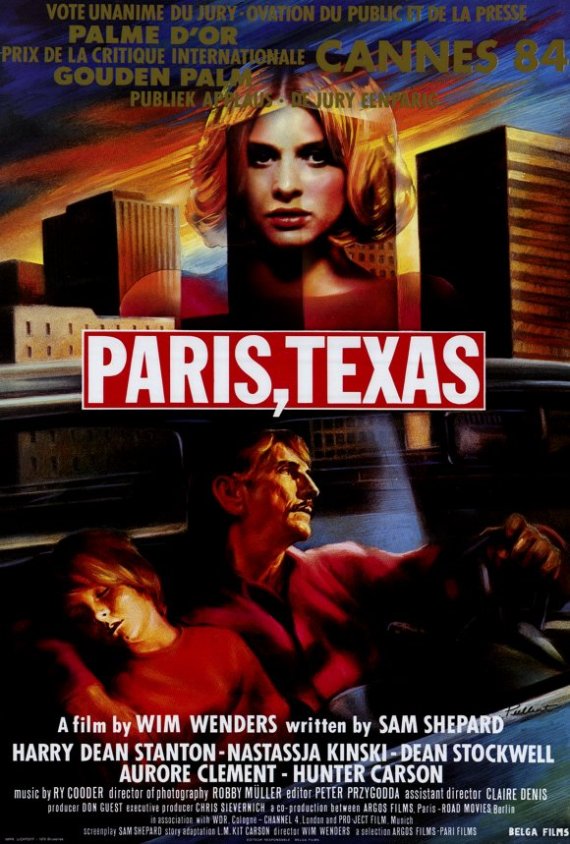

Paris, Texas (1984)

Today’s cinema adventure: Paris, Texas, director Wim Wenders’ elegiac drama that swept the 1984 Cannes Film Festival and has consistently remained on most critics’ “Best of” lists ever since. Adapted by L.M. Kit Carson from a screenplay by esteemed playwright Sam Shepard, it tells the story of Travis, a middle-aged man who walks out of the Texas desert after disappearing for four years and, after reuniting with his brother’s family, slowly begins the effort of restoring his shattered life. Through this simple synopsis, Wenders executes a masterful, character-driven exploration of subjects, allowing the mystery of Travis’ past to unfold through the players’ interactions and reminiscences as they take awkward steps to move towards an uncertain future- and using the microcosmic drama to stir powerfully resonant themes and conjure deep, universal emotions. A collection of superb performances makes it all work beautifully, from veteran character actor Dean Stockwell as Travis’ well-meaning brother to newcomer Hunter Carson (son of the film’s screenwriter Carson and actress Karen Black) as the child rebuilding a relationship with a father he doesn’t remember; Nastassja Kinski, whose star turn doesn’t come until late in the film, beautifully captures the emotional fragility of a woman confronted with a past she has tried to forget (though I can’t help nit-picking that her German accent sometimes distorts an otherwise acceptable Texas drawl). It is, however, the remarkable presence of Harry Dean Stanton, as Travis, upon which the film hangs: from the opening moments when he purposefully stumbles out of the blasted Texas landscape, he is utterly compelling, allowing his droopy, hang-dog features and his simple, unaffected delivery to express a dazzlingly complex spectrum of emotions. It is a performance which few actors could accomplish, and the fact that it was not even nominated for an Oscar is one of those glaring omissions that makes the entire idea of Hollywood awards seem suspect and vaguely ridiculous. Beyond the cerebral and emotional riches provided by Paris, Texas, it delivers a visual beauty thanks to the stunning cinematography of longtime Wenders collaborator Robby Müller, which captures a remarkable array of iconic American backdrops- the dusty vastness of the southwestern desert, the scenic experiences of the endless cross-country highway, the bland familiarity of suburbia, and the contrasting elegance and squalor of the big city- giving this jointly-French-and-German-produced film a distinctly American flavor rarely captured by domestic cinema. Despite these lavish praises, this movie is probably not for everyone: viewers with a short attention span may find the leisurely pace a bit grueling (particularly in the climactic sequence, which is comprised mostly of long, lamenting monologues performed in a claustrophobic setting), and those who seek a clear-cut, definitive resolution from their entertainment may be left unsatisfied by the mixed emotions which cascade around its ambiguous conclusion. Nevertheless, it is hard to imagine a more exemplary piece of filmmaking than Paris, Texas, and it is easy to see why it became one of the most influential and revered pieces of cinema to come out of the eighties.

Crimes of Passion (1984)

Today’s cinema adventure “Crimes of Passion, the controversial 1984 sexual thriller by cinematic bad-boy Ken Russell, centered around a hard-driven career woman who gets her sexual validation moonlighting- in disguise- as a streetwalker named “China Blue.” With his characteristic excess, both in his artistic style and his explicit depiction of sex, Russell uses the titillating scenario to explore a variety of psycho-sexual themes, portraying attitudes and behavior at both ends of the spectrum between depravity and repression; provoking numerous questions about the relationships between love, sex, truth, fantasy, shame, guilt and redemption; and exploring the difficulty of overcoming fear and immaturity in order to form an honest human connection. A heady and ambitious agenda, to be sure, and whether or not Russell and his screenwriter/producer, Barry Sandler, have succeeded in achieving it is still the subject of much debate- as with most of the director’s work, the response of critics and audiences is sharply divided between “hate it” or “love it.” My take: Russell’s madness has a method, and with his almost cartoonish depiction of the erotic underworld inhabited by China Blue and her clientele, he highlights the absurdity of our sexual prejudices and suggests that we have much more to fear from the consequences of repressing our natural desires. Helping considerably towards this goal is Kathleen Turner, at the height of her sexual appeal, delivering a remarkable performance infused not only with the necessary gleeful eroticism but also the vulnerability of a woman terrified by emotional intimacy. Also superb is Anthony Perkins, in an underrated turn as a seedy street preacher whose shame over his own pornographic impulses leads him to an obsession with “saving” China Blue; though derided by many critics as “over-the-top,” Perkins’ work here is frighteningly accurate, which should be clear to anyone who has ever had an encounter with a dangerously schizophrenic denizen of the streets. These two share several delicious scenes together, skillfully enacting an ongoing point/counterpoint about sexual morality that underscores the movie’s themes and provides many of its most delightfully melodramatic moments. Not as proficient is John Laughlin as a naive young husband whose failing marriage leads him to China Blue’s bed- but despite his somewhat stilted acting, his sincerity shines through enough to provide the necessary relief from the darkness of the skid row surroundings. Other notable elements include the costumes, scenic design and cinematography, all of which brilliantly contrast between the garish night-time world of the red-light district and the bland suburban daylight of the film’s other scenes- the two worlds seem almost as if they have been spliced together from two different films. Less successful- perhaps the film’s biggest flaw, really- is the tinny electronic score (provided by Rick Wakeman of the band Yes), which may have seemed like a good idea at the time but now provides a ludicrously dated atmosphere in a film that might otherwise seem almost timeless. Nevertheless, Russell’s film retains a surprising depth and resonance despite- or perhaps because of- the sensationalism of its hyper-sexual surface, and even if there are times when his intellectualism threatens to undermine the plot or his exploitative excess threatens to alienate his audience, the compelling performances of his two stars succeed in maintaining the emotional connection that is necessary to ensure the slow build of suspense into the climactic scenes. Overall, though Crimes of Passion lacks the audacious mastery that made instant classics of some of Russell’s earlier works, it still packs a powerful punch, melding sensuality with horror and humor with high drama, and ultimately- in my view anyway- standing as one of the most memorable and unique films of the eighties.

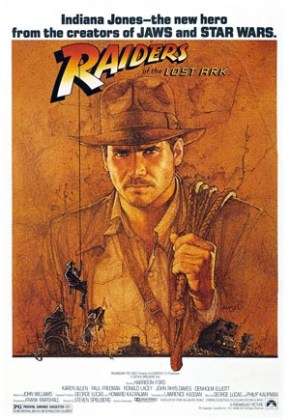

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Today’s cinema adventure: Raiders of the Lost Ark, Steven Spielberg’s 1981 action-adventure-fantasy paying homage to- and gently spoofing- the cliffhanger serials of the thirties and forties- but with the benefit of a mega-budget and then-state-of-the-art special effects, courtesy of the powerhouse production provided by George Lucas. It would be pointless and impossible for me to write anything like a critique of this film- it has passed beyond the realm of review and into cinema legend, and did so almost immediately upon release, becoming an instant classic and creating a brand new archetypal hero in Indiana Jones, the mercenary archaeologist/adventurer at its center. It spawned a franchise of three (mostly inferior) sequels, countless unworthy imitations, and it made an icon of its star, Harrison Ford, whose roguish charm melds so perfectly into his character that it is literally impossible to imagine anyone else playing it. And, on a personal level, it became a major touchstone in my young manhood, a cultural phenomenon into which I dove headlong, making any sort of objective viewpoint about the movie completely irrelevant. What I will say is that, after several years since my last viewing, the movie holds up brilliantly, seeming just as fresh and fun as it was 30 years ago, managing a precarious balancing act between the serious tone necessary to sustain its premise and the sly, unapologetic goofiness that keeps it fun and reminds us, constantly, that it’s only a movie- aided immeasurably by John Williams’ rousing, multi-faceted score, with its now-familiar thematic march, which is surely one of the greatest examples of the use of music to support and drive a film. In addition, it struck me this time around that this movie represents Spielberg’s direction at its finest, the work of a young artist at the height of his powers, using his skills for the sheer joy of it- completely without pretense or the need to make any kind of statement, merely an expression of his own love of movie magic and an invitation to us all to share it with him. Sure, you can quibble forever over the myriad gaps in logic and continuity that render the entire story ridiculous- an intentional element drawn from the grade-Z crowd-pleasers that inspired it- or you can point out the numerous visual and stylistic references to classic movies like Treasure of the Sierra Madre or Lawrence of Arabia, from which the director derived his filmmaking vocabulary; but those things don’t matter, in the final analysis. “Raiders” stands on its own as a great achievement in filmmaking, a timeless tribute to movies themselves and a magic potion to rekindle- even if only for a couple of hours- the adventurous imagination of the fourteen-year-old in us all.