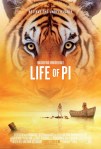

Today’s cinema adventure: Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock’s classic 1960 shocker about a series of gruesome murders at an out-of-the-way roadside motel. Based on Robert Bloch’s novel of the same name, which was in turn inspired by the real-life case of Ed Gein, a deranged Wisconsin farmer who stole numerous bodies from a local cemetery and murdered several women while living with the corpse of his long-deceased mother, it was heavily deplored by most- but not all- critics at the time. Thanks, however, to Hitchcock’s sensationalistic marketing strategies and his popularity as the host of the then-current TV anthology series, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, it was an enormous box office success; it played an important role in changing the film industry’s outdated standards for “acceptable” subject matter and spawned scores of imitators, paving the way for the “slasher” sub-genre of horror films and wielding immeasurable influence over generations of subsequent filmmakers. Its critical reputation quickly grew, and it is now almost universally recognized as one of the greatest movies of all time, or certainly, at least, one of the most important.

Psycho is one of those films that is so widely known as to be ingrained in the cultural consciousness; it is hard to imagine that anyone in 2012, whether they have actually seen it or not, would be unfamiliar with the once-notorious plot twist that prompted Hitchcock to implore movie audiences not to reveal the ending after they had seen it. However, on the assumption that there are such people out there who might be reading this, I offer fair warning that beyond this point you will encounter “spoilers,” and you might want to stop here. Psycho begins in Phoenix, Arizona, with a lunchtime tryst in a cheap hotel between Marion, a secretary, and Sam, her divorced lover from out of town, who cannot afford to marry her because of his crippling alimony payments. Later, at the real estate office where she works, Marion’s boss entrusts her with $40,000 in cash, instructing her to take it to the bank on her way home; seeing a chance to put an end to the dead-end arrangement of her love life, she instead packs a bag and takes the money to start a new life with Sam, heading down the highway towards Fairvale, the small California town in which he lives. When a blinding rainstorm makes driving unsafe, she stops for the night at an isolated motel off the main highway, operated by an awkward but sweet young man, Norman, who lives with his elderly mother in a Victorian house on the hill behind the office. Norman is warm and polite, inviting his weary guest to join him at the house for a light dinner; but after Marion overhears a heated argument between her host and his mother, who angrily refuses to let him bring a female guest into her home, he instead brings a plate of sandwiches to the motel, and the two of them share a meal in the office parlor. During their conversation, Norman tells Marion that his mother is mentally disturbed and prone to fits of anger, but that he feels obliged to care for her, though it means sacrificing his own freedom, because “a boy’s best friend is his mother.” When Marion returns to her room, she decides to take a relaxing shower before going to bed- only to have it brutally cut short when the dark figure of Norman’s mother creeps into the room and stabs her to death with a butcher knife. Upon discovering his mother’s savagery, Norman decides to do the dutiful thing and clean up the mess, disposing of the body and all evidence of Marion’s ill-fated visit- including the stolen cash, still wrapped in a newspaper- in a nearby swamp. A few days later, in nearby Fairvale, Sam is visited in his hardware store by Lila, Marion’s sister, who has come in hopes that she will find her missing sibling there; they are quickly joined by a private investigator named Arbogast, hired by Marion’s boss to retrieve the stolen money without involving the authorities. When it becomes clear that Sam is as ignorant as they are to Marion’s whereabouts, Arbogast begins to canvas the area looking for signs of the missing girl’s presence; eventually he arrives at Norman’s motel, where he quickly deduces the young man is hiding something. After sharing his suspicions in a phone call to Sam and Lila, he sneaks into the house in search of Norman’s mother, thinking to get more information from her, and quickly becomes the next victim in the deranged woman’s bloody rampage. With Arbogast’s disappearance, Sam and Lila decide to take the investigation into their own hands, and head to the motel to seek answers- but neither is prepared for the dark secrets they will uncover before they can solve the mystery of Marion’s disappearance.

As detailed in the current film, Hitchcock, Psycho was a major departure for the legendary director, a small-budget, black-and-white, sordid and sensationalistic shock piece that no studio wanted to touch. Even with his prestigious reputation and his popular status as a television star in his own right, Hitchcock had to finance the film himself in order to make it. It was a risky venture, to say the least, but one which paid off for him in a very big way; the film broke box office records, becoming the highest-grossing release of his career and making him a millionaire. Its success forced critics to re-evaluate it- those who had been initially dismissive of it as a tastelessly lurid, low-budget shocker, beneath the usual standards of the “master of suspense,” soon praised it enthusiastically and included it on their “best of the year” lists, and it was ultimately nominated for numerous awards (including four Oscars). In the end, Psycho rewarded its director with the late-life revitalization of an already extraordinary career, made him an even greater power player than he had been before, shattered industry taboos against depictions of sexual and violent content, and won him a new generation of fans- and all at a cost of less than a million dollars.

It was no accident of fate, either; the canny Hitchcock understood exactly what he was doing, and he exerted his meticulous craftsmanship on every aspect of the production in order to achieve the kind of visceral, ground-breaking effect he knew would electrify audiences seeking a new kind of thrill. To this end, he had chosen his source material for its deeply unsettling subject matter, as well as for its deliberate and merciless manipulation of readers’ sympathies. To keep the budget down, he chose to shoot in black-and-white, using mostly the personnel from his TV series; a few trusted collaborators, however, were also hired, such as graphic artist Saul Bass, editor George Tomasini, and composer Bernard Herrmann, whose previous contributions to his film work had proven invaluable. He cast the roles with familiar and experienced actors, but avoided using big stars, both to keep salaries down and to prevent personality from overshadowing the story; and- after rejecting an initial screenplay by James Cavanaugh, who had written several scripts for his TV series- he hired screenwriter Joseph Stefano (who had only one previous writing credit, but possessed extensive personal experience as a patient in psychotherapy) to adapt Bloch’s book for the screen.

Stefano’s screenplay remains fairly faithful to the novel in its plot, though a few changes were made to accommodate the requirements of the cinematic medium; most significantly, the central character of Norman Bates was transformed from an overweight, middle-aged alcoholic to a youthful, squeaky-clean boy-next-door. This was Hitchcock’s direct input, designed to make the character more readily sympathetic to the audience; his likability was crucial for the director’s purpose, which involved tricking the audience- and here’s the big spoiler, for those who care- into identifying with a psychotic murderer. Indeed, the narrative of Psycho is one piece of trickery after another, enhanced by Hitchcock’s casting of his biggest star, Janet Leigh, as a character who is killed off a third of the way through the movie, and his other biggest star, Anthony Perkins, as someone who not only covers up her death but ultimately turns out to be her killer. The crucial plot twist- that Norman’s mother is in fact her stolen, mummified corpse and that he himself suffers from a split personality in which he commits the murders while assuming her identity- is kept hidden by shrouding the mother figure in mystery, keeping her offscreen except in shadow, silhouette, or oblique camera angles, and hearing her conversations with Norman from off-camera- which has the added effect of making the audience feel like an eavesdropper. This is another important element of Psycho, the sense that we are clandestine observers of some forbidden ritual, and it of course constitutes the biggest trick of all- Hitchcock turns us into voyeurs, getting our cheap thrills by peeking through windows, listening at doors, and sneaking into private rooms. It’s a now-familiar tactic, used extensively by filmmakers wishing to enhance our connection to their subjects and to subvert our affectations of propriety, and Hitchcock was certainly not the first to use it; but in Psycho, he brought it out of the art house, where European and avant-garde directors had been experimenting with it, and into the popular cinema, thrusting mass audiences into a wholly subjective experience and smashing through the “fourth wall” of the camera by making it into a substitute for the eye itself. We are subtly drawn into this personalized experience from the very beginning of the film, when the camera slowly zooms from a panoramic view of the Phoenix skyline through the window of a darkened hotel room to spy on Sam and Marion as they finish their midday liaison; throughout the rest of the movie we are kept in the action with the heavy use of point-of-view shots, scenes filmed through doors, windows, phone booths, and even a peep hole, and the theme of clandestine observation is layered in by the characters themselves, who overhear, watch, question, and spy on the actions of others throughout the film.

This voyeuristic approach was nothing new for Hitchcock, but rather the culmination of a motif with which he had long been fascinated; throughout his career he had developed techniques for enhancing the audience’s identification with the lens, emulating the natural movement of the human gaze with his camera, using the same point-of-view perspectives and many of the other tricks which would become the dominant mise-en-scène of Psycho. Likewise, many other of his favorite thematic elements are contained within the narrative- doubtless one of the reasons he was attracted to the material. Many of Hitchcock’s films feature problematic relationships with domineering parents (sometimes played for laughs, but always containing a decidedly dark undercurrent); his heroes are frequently flawed, even seriously broken, and often unsympathetic, while his villains are usually charming and likable; law enforcement figures are mostly ineffectual or downright incompetent, and “polite” or “normal” society is generally seen to be a hypocritical veneer for hiding any number of unsavory character traits; and, of course, there is the ever-present icy blond, a beacon of inaccessible beauty, repressed sexuality, and, usually, possessed of a compromised virtue which must be regained. All of these are deeply embedded in the fabric of Psycho– there are even two icy blonds- and used relentlessly to undermine the audience’s ingrained expectations. The heroine is a thief, but her victim is a fatuous boor, and her motives are understandable, if misguided; her sister is prudish and severe, while her boyfriend is morose and belligerent; the police are condescending and dismissive, the private eye pushy and sardonic; Norman, however, is shy, kind and endearing, even if his hobby of stuffing birds is a little weird, and he is, of course, the epitome of the dutiful son. In any standard narrative, it would be clear where our sympathies should lie, but here everything is turned upside down; we root for Marion, and when she is suddenly and cruelly taken from us, we easily transfer our affections to her killer. We make this willing shift partly because we do not yet know he is guilty, it’s true, but Hitchcock has built his trap so craftily that we would likely take the leap even if we did. By the end of the film, the director has successfully made us emotional accomplices to both grand larceny and murder, and with his final shot of Marion’s car being pulled from the mud, a lifeless shell representing all that is left of her naive hope for a happy future, he rubs our faces in it.

There is another layer to all this subversive irony, though, beyond just a trickster’s impulse to make us feel dirty. Our willingness to empathize with first a thief, then a killer, is grounded in what we think we see, what we want to believe, and what we have been trained to expect. There are plenty of warnings- all the information we need to see the truth is plainly given as we go along, and yet we choose to bestow our sympathy based on romantic illusion. We want the pretty, decent Marion to be able to “buy off unhappiness,” and we assume the boyish, mild-mannered Norman to be the innocent victim of his mother’s cruelty- from which we hope he can somehow break free without repercussions for his role in covering up her crimes. This emotional manipulation is achieved by Hitchcock’s mastery of image; he carefully arranges what we see and hear in order to place us in conflict with ourselves, torn between our direct instinctive reactions and our intellectual assessment. It’s a master con, made possible because of our tendency to mistake image for reality, but we buy into it willingly even as Hitchcock tauntingly tips us off all the way through. Just as he gives us indications throughout that could easily lead us to recognize the truth about Norman and his mother, he inundates us with reminders about the relationship between image and reality; virtually every scene features mirrors or windows which allow us to see both the characters and their reflections, and most of the plot’s complications arise as a result of decisions based on faulty perception of the surface. Marion is able to steal the cash because she seems trustworthy, she trusts Norman because he seems harmless, and everyone believes in his mother’s existence because she seems to be in the house. Even the town sheriff, upon learning about the supposed involvement of a woman he knows to have been dead for years, is uninterested in investigating further because he forms an explanation that satisfies his assumptions. In the end, Psycho is not about solving mysteries or exposing the pathology of a homicidal personality; it is an examination of- and a warning against- the dangers of living in a fantasy derived from what we want to believe. We, as the audience, arrange the images to tell the story we expect to see, and when we are brutally reminded by Marion’s ignoble exit from the scenario that all is not what it seems, we fall right back into the clutches of illusion by transferring our sympathies to Norman. In the climactic revelation, the sight of Norman, shrieking maniacally in his cheap wig and dress as Sam wrestles him into submission and his desperate illusions fall away along with the last vestige of his sanity, we cannot even comfort ourselves that we had no way to see it coming. It may be a shock, but when we re-examine what has gone before, it is not really a surprise. We let ourselves be deluded every step of the way, allowing our preconceived judgments color our perceptions; or to put it another way, to paraphrase a key subject from the parlor discussion between Marion and Norman, we have stepped into our own private trap. This is the true heart of the film- the self-created cage of perception that traps us each and defines the way we see the world. The image we embrace becomes identified as our reality, but as Hitchcock loves to remind us- and nowhere more vividly than in Psycho– this is an illusion, and one which can lead to the direst of consequences.

With so many volumes having been written about Psycho, it was not my intent to add much to it; clearly, however, I have been caught up in the spell of this much-discussed classic. Something about this movie begs to be analyzed, explored, and revisited time and again. There is so much here to stimulate, to intrigue, to perplex. One can watch the film simply to revel in Hitchcock’s pure technical mastery: the aforementioned ways in which he invites us to participate in his own voyeurism; his ability to build tension with his deliberate pacing and editing, utilizing long, leisurely scenes interrupted by sharp, violent shocks that echo the stabbing of the knife; his use of visual means to keep us off-balance and on edge, such as dramatic camera angles, uncomfortably extreme close-ups, overhead shots, and other signature Hitchcock touches; and of course there is the justly famous shower scene, a 45-second collage of spliced film that terrorized the entire culture in 1960 and still inspires a particular kind of fear today. You could also focus on Bernard Herrmann’s iconic musical score, a haunting and nerve-jangling composition for strings that Hitchcock himself credited for being 33% responsible for the film’s effectiveness and has been consistently placed at or near the top on lists of the greatest film soundtracks ever written; during the opening credits, you can marvel at the way the music is complemented by the title sequence created by the great Saul Bass, a no-less-iconic jumble of broken, intersecting lines that suggest the jagged turmoil of a disturbed mind as they spell out the pertinent names and assignments of the movie’s participants.

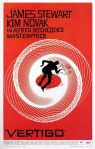

Of course, you can also reap the rewards of Psycho if you dedicate a viewing entirely to an appreciation of the performances. Anthony Perkins’ work here is as fine an example of screen acting as you are ever likely to see, a masterpiece of understatement with subtle nuances revealing themselves upon every repeat viewing. It was a role that matched him perfectly, allowing an intertwining of personal experience and fictional subtext that gives Norman a rare level of authenticity and makes him as heartbreaking as he is disturbing; though the character permanently defined his career and resulted in years of typecasting, it provided the young actor with a chance to leave a legacy the likes of which few others can claim. Often overlooked, but no less definitive, is Janet Leigh’s outstanding work as Marion Crane; offering us an utterly convincing portrait of an everyday working girl, smart and clearly independent, but hiding a desperate longing to find the happier life of which she dreams, she wins us over immediately- and not only because of the obvious sex appeal of the opening scene, in which she helped to break down the so-called “decency code” by appearing in only a bra and a slip- and makes us keenly feel along with her the frustration of her mundane life, the irresistible thrill of her impromptu escape, and the mounting distress and paranoia that comes as she begins to recognize the consequences of her choice. She is powerfully likable, which makes it doubly cruel when she is abruptly taken from us; this was Hitchcock’s goal, of course, carefully orchestrated by expanding Marion’s story from the brief episode it comprises in the original novel and by casting his most widely-known star in the role. Leigh was his first choice, and she eagerly agreed to the project without even reading the script or discussing her salary; she was rewarded for her enthusiasm with an Oscar nomination, and, like her co-star, she created an unforgettable piece of cinema history, a rich and layered performance that is so good precisely because it contains no overt histrionics with which to call attention to itself. The rest of the cast, though their roles are not as complex in dimension, are equally memorable- despite the fact that the director was vocal in his dissatisfaction with John Gavin (whom he referred to as “the stiff”) and that he was, by all reports, punishing Vera Miles for her abandonment of his earlier Vertigo (she became pregnant and bowed out before filming began, forcing Hitchcock to replace her with Kim Novak) by making her character here as unappealing as possible. As Sam and Lila, respectively, both performers actually provide exactly the right qualities to their roles, making it impossible to imagine the film any other way; and, rounding out the main cast as Arbogast, Martin Balsam is likewise a perfect fit, giving us a canny portrait of a no-nonsense professional whose blunt and rumpled exterior belie the crafty shrewdness underneath.

There is so much to write about Psycho; I could go on with discussions of the layered themes and the techniques used by Hitchcock to explore them, or the brilliance of the stark black-and-white photography and its visual symphony of light and shadow, the contrast between the unglamorous, utilitarian settings and the austere design of the now-famous Edward-Hopper-inspired house that glowers down over the motel- the list is inexhaustible. Similarly, I could write volumes about the history surrounding the film. The battles with the censors over such things as the raciness of the opening hotel room scene, the use of the word “transvestite,” and the inclusion of a toilet (never before shown in an American film); the painstaking creation of the shower scene, which took a week to film, and generated obvious controversy upon release as well as much future argument about factors like whether it was Leigh or a body double that was used in the majority of its shots or the extent of involvement by Saul Bass, who drew the storyboards for the sequence but later claimed to have directed it in its entirety; the depth of contribution by Hitchcock’s wife and creative partner, Alma Reville, who- as she had on every film of her husband’s career- collaborated on every aspect of the movie from pre-production to final editing; all these things and more are legendary chapters in the story of Psycho, and you can (and should) read about them in so many other places that it is unnecessary to take any more time with them here.

The most pressing issue regarding Psycho, perhaps, for the “typical” modern viewer, who may have little scholarly interest in the film as a piece of cinematic art history and probably doesn’t care about the virtually unfathomable influence it has had upon every horror film that came after it, is simply whether or not it is still holds up. Does this seminal, deceptively simple thriller live up to its reputation for inducing terror and inspiring nightmares for weeks after seeing it? The answer, honestly, is probably not. By today’s standards, even the most squeamish viewer is unlikely to find any of the film’s once-controversial violence hard to take; the gore factor is minimal, even in the famous shower scene with its chocolate-syrup blood, and, with a mere two killings taking place onscreen, the body count is decidedly low. Taking this into account, along with the fact that it is virtually impossible to go into the movie without knowing its twist ending (or at least being familiar enough with its many imitators that it becomes easy to spot from very early on), Psycho is unlikely to generate many shocks with jaded modern audiences, and indeed is more apt to produce laughter- a development, incidentally, that would likely have pleased Hitchcock, who always claimed that the film was meant to be a very dark comedy. Still, even if it has lost its power to scare us outright, it nevertheless casts an eerie and unsettling spell; even with its now-tame level of splatter, the shower scene is a deeply disturbing psychological jolt which plays on our most primal fears and reminds us of our innate vulnerability in the most common and universal of activities, and there is an undeniable creepiness that pervades the scenario, compounding as it progresses so that the Bates Motel and its adjoining house become more ominous and sinister in the bright light of day than in the earlier scenes at night. Furthermore, instead of a neat and positive happy ending, Hitchcock leaves us with the mocking reminder that the world’s evil can be temporarily vanquished, but it will still remain, hidden in the most innocent-seeming of places, awaiting its opportunity to catch us unprepared; the final sequence of Norman, sitting alone in his cell as we hear “mother’s” voice in his mind, undermines any sense of safe, comfortable normalcy that might have been re-established by the previous explanatory denouement in which the smugly self-satisfied forensic psychiatrist unfolds his pat diagnosis of the murderer’s tormented psyche, and the final aforementioned shot of Marion’s car being pulled from the mud reminds us of the ugly reality of her senseless death- defying any attempt that might be made to assign it a meaning or purpose. There is no comfort here, only tragedy and a chaos so deeply imbedded it can never be excised. The power of these observations is as tangible today as it was five decades ago, whether or not Psycho frightens on a direct level, and any viewer seeking more than a cheap, visceral thrill will soon be drawn into the movie’s seductive web of delusion and consequence. In short, Psycho may be better approached by the modern viewer as a psycho-drama, without expectations of blood-chilling fright and nausea-inducing carnage; indeed, it can be viewed, as its director did, as a comedic exploration of the fantasies in which we wrap ourselves and the mishaps in which they might result, though admittedly this requires a particularly morbid sense of humor. In truth, of course, Psycho was never really meant to be a horror film, though it may have horrified; as in all of Hitchcock’s work, the real purpose is hidden behind the “McGuffin,” his term for the seemingly vital element around which his plots appear to revolve but which is actually a ruse through which his true concerns can be explored. The McGuffin here is the mystery itself- ultimately the theft, the murders, and the psychotic delusions of the central character are all merely smoke and mirrors for Hitchcock’s master plan, in which he pulls the rug right out from underneath us and leaves us grasping for support that is no longer there. Though he dresses Psycho in the trappings of the horror genre, its real riches lie beneath that exploitative exterior, and are ultimately more profoundly upsetting than any cheap momentary shock tactics could ever be. On this level, from which it has always, truly, derived its greatness, Psycho is as fresh and relevant as the day it was released, and remains a must-see requirement for anyone who considers themselves even a casual film fan. Personally, I first saw it at the age of ten, alone in my second-story bedroom on a tiny black-and-white TV screen. It didn’t scare me, much, even at that tender age, but it certainly made a deep impression, and it most likely provided the single film experience that started me on my lifetime cinema adventure. I’ve since seen it an uncountable number of times, and each time I never fail to be drawn in and to discover something new to consider. If you are lucky, Psycho will hook you the way it hooked me; at the very least, it will make you think twice about leaving the bathroom door unlocked the next time you shower in a motel.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0054215/