Today’s cinema adventure: My Week With Marilyn, the wistful 2011 biopic based on Colin Clark’s memoir, The Prince, the Showgirl, and Me, which detailed the author’s brief relationship with iconic starlet Marilyn Monroe during the turbulent filming of The Prince and the Showgirl with actor/director Sir Laurence Olivier. Whereas many film biographies attempt to shed light on their subjects by presenting their life in its entirety, this charming true-life romance focuses instead on a short episode, using it as prism to cast insight into the legendary actress and her contemporaries. As a result, the film has an intimacy and an authenticity lacking in most Hollywood bios, and the narrowing of focus allows the performers to explore the nuances of their real-life characters with much greater depth and detail, heightening the illusion that we are watching real people instead of the larger-than-life caricatures to which we are so often subjected. Those performers, without exception, rise to the occasion: the entire ensemble clearly relishes its chance to embody this slice of mid-century mythology. The much-lauded Michelle Williams is largely successful in capturing the enigmatic persona that made Marilyn the biggest star in the world; she gives us the contrasting blend of sensuality and insecurity we expect but infuses it with a humanity that allows us to perceive the underlying causes of her fragility and need for validation, as well as the irresistible charm that won the hearts of so many. To be sure, her transformation is less than total- her physical attributes are not quite right, and her bearing sometimes seems mote timid than self-assured- but, of course, she is ultimately an actress interpreting a role, not a reincarnation, and as such she deserves much praise for conveying the essence of an oft-imitated woman who was, in fact, inimitable. Less glamorous, but perhaps even more impressive, is Kenneth Branagh’s work as Olivier which likewise captures the great actor’s outward persona with remarkable accuracy while showing the inner landscape of a man struggling to keep his place at the top in the face of changing standards in the art he has mastered for so long; Olivier was not only an early mentor for Branagh but an actor with whom his own career has often been compared, so he seems well-suited to the daunting task of personifying the legendary thespian- a task which he clearly relishes, recreating Olivier’s physicality and vocal patterns with intimate familiarity with0ut resorting to out-and-out mimicry, and treating his subject with obvious respect even when portraying some of his less attractive facets. As these two enact their clash of titans, they are surrounded by a host of worthy supporting performances, including Julia Ormond’s brief but canny portrayal of Vivien Leigh, Emma Watson’s decidedly non-Hermoine-esque turn as a wardrobe girl, and the always magisterial Dame Judi Dench as the always magisterial Dame Sybil Thorndike; but special praise should be reserved for Eddie Redmayne, who, stuck with the potentially thankless role of providing a foil for his co-stars, manages also to provide a solid ground for the proceedings by giving a quietly convincing performance as the young film crewman coming of age in the shadow of giants, and never lets us quite forget that this is, after all, his story. With all this great acting going on, it’s easy to overlook the film’s other pleasures- the meticulous costume and scene design; the rich, golden-hued cinematography by Ben Smithard; the understated archness of the screenplay by Adrian Hodges- all overseen by the steady hand of first-time director Simon Curtis, whose wise approach here is to step back and let all these elements leave their marks without the unnecessary assistance of showy cinematic trickery. The end result is a movie which, like the famous figure at its center, is lovely, effervescent, and hauntingly sad. It does not promise nor does it try to present the final word on Marilyn- or Olivier, for that matter- and for that very reason, probably comes closer to giving us a truthful, fair vision of these two legends than any scandal-raking exposé could hope to deliver.

Category Archives: Romance

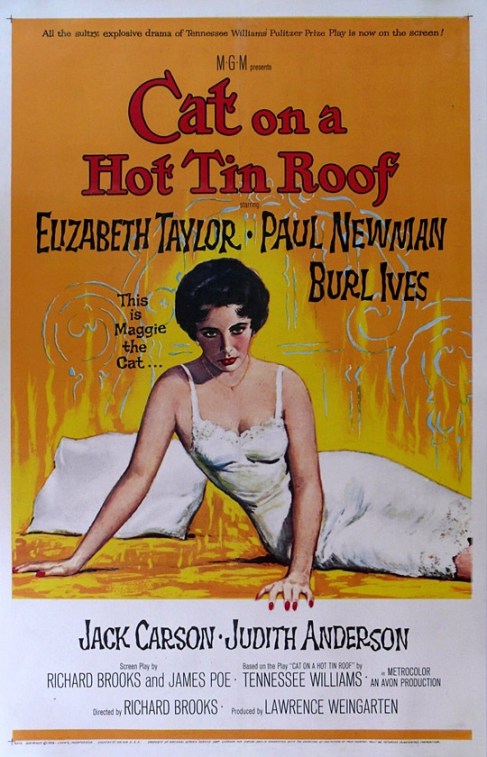

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

Today’s cinema adventure: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the 1958 screen adaptation of the Pulitzer-winning drama by playwright Tennessee Williams. Set on the plantation of “Big Daddy” Pollitt, a Southern cotton tycoon who has just been diagnosed with terminal cancer, the plot revolves around the angling of the patriarch’s family for control of his estate and the various conflicts between them, particularly between the heavy-drinking youngest son, Brick, and his wife, Maggie, whose relationship has gone cold over a recent tragedy- and a guilty secret. Produced at the height of the glamorous era of late-fifties American cinema, and starring two of Hollywood’s biggest stars of the time- Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman- it was an A-list prestige production and one of the ten biggest box office hits of the year, yet both Williams and leading man Newman expressed disappointment in the final product; indeed, the playwright publicly distanced himself from the film, even telling potential audiences to stay home. Their reticence, shared by numerous critics and literary purists, was due to the studio censorship, influenced by the then-still-observed Hays Code, which led to the removal of the play’s homosexual references- rendering the central conflict of between the two leads vague and unconvincing- and to the extensive rewriting of the final act to allow for a more “satisfying” reconciliation between Big Daddy and his alcoholic son. While it is certainly true that this filmed version of Williams’ personal favorite play was substantially tamed down from its original form, it nevertheless provided plenty of controversy in 1958: even without overt reference to homosexuality, savvy viewers could certainly still pick up on the unspoken truth behind Brick’s gnawing shame; and puritanical eyebrows were raised in abundance over the sexual frankness of the dialogue (not to mention the sultry chemistry between the stars, surely two of the most beautiful people ever to step in front of a camera). These controversial elements no doubt contributed greatly to the film’s popularity at the time; but by today’s standards, of course, its content would barely warrant a PG rating. What then, if anything, is there to recommend this venerable artifact of mid-century sophistication to modern audiences? To begin with, the sets, the costumes, the cinematography- the entire production- is everything you would expect of a high-budget, top-notch MGM product; but the same is true of many infinitely less watchable films from the same era. What really matters here is the material. Even watered-down Williams is a treat to see and hear, particularly in the hands of a cast capable of bringing out the rich, musical literacy and the deep, resonant emotional landscape of his text; and though director Richard Brooks (who also co-wrote the sanitized screenplay with James Poe) crafted a relatively uninspired film version, cinematically speaking- particularly when contrasted with other Williams adaptations of the time, such as the earlier classic, A Streetcar Named Desire– he clearly had a strong enough understanding of the piece to evoke uniformly superb performances from his players. Recreating his role from the Broadway production, Burl Ives dominates his every scene- and appropriately so- as Big Daddy, overbearing all before him with a grim, determined Southern smile even when most assaulted by pain, whether emotional or physical. Matched against him is the great Judith Anderson, oddly cast but highly effective as Big Mama, creating a sympathetic portrait of a woman, hardened but unbeaten by a lifetime under her husband’s imposing shadow, desperately clinging to the illusions she has worked to maintain for herself and her family. Jack Carson is likable as older brother Gooper despite the ineffectual disinterest of a character forever dominated by the others around him; and, as his wife Mae, Madeleine Sherwood (another veteran of the Broadway production) balances him by being equally dis-likable, an embodiment of mean-spirited pettiness, hypocrisy and self-righteous entitlement that serves as the closest thing in the piece to a villain. Of course, all this stellar supporting work would be meaningless without equally strong performances from the leads, and the two iconic stars here give performances that rank among the finest of their careers. As Brick, Newman proved once and for all that his ability as an actor was as formidable as his steely-blue-eyed good looks; he gives a remarkable and definitive interpretation of the character, playing against those leading-man-looks to bring out the ugliness of Brick’s dissolute bitterness- the high-handed and deliberate cruelty, the obstinate refusal to face his demons, the willfully self-destructive embrace of his alcoholism- without ever completely obscuring his underlying sensitivity and compassion, creating a complete portrait of a good man crippled (both literally and metaphorically) by the effects of failure, regret, and shame. The keystone performance, however, comes from Taylor, at the peak of her astonishing beauty and the beginning of her reign as one of Hollywood’s most glamorous and beloved stars. It would be easy to play Maggie “the Cat” as an ambitious, tawdry social climber bent only on claiming the family fortune of a man she has married for money, but Taylor makes her so much more: she not only radiates the aching sexuality of a woman too long neglected, but also the determination and candor which make it clear that she alone has the strength to be Big Daddy’s true successor as the dominant force in this family, coupled with the earnest feeling that makes it possible for us to believe, in the end, that she has the power to “make the lie true.” That, ultimately, is what Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is about: in a world full of “mendacity,” it takes passion and, yes, love to make the difference between truth and illusion. This first and still most authentic film version, with all its Technicolor gloss and its soundstage artificiality, is Hollywood illusion at its most persuasive- but thanks to Miss Taylor and the rest of its remarkable cast, it has the real ring of truth about it, and that is what makes it a classic.